Between Sustainability and Growth Critique: Why I Study Agreements in SMEs

Course Essay at Lappeenranta-Lahti University of Technology LUT - A350AJ700 Sustainability and Impact in Business Research

Positioning my research to understand impact – On the discourses of sustainability and impact of economic growth on the natural environment — Assignment: Reflection paper 2/5

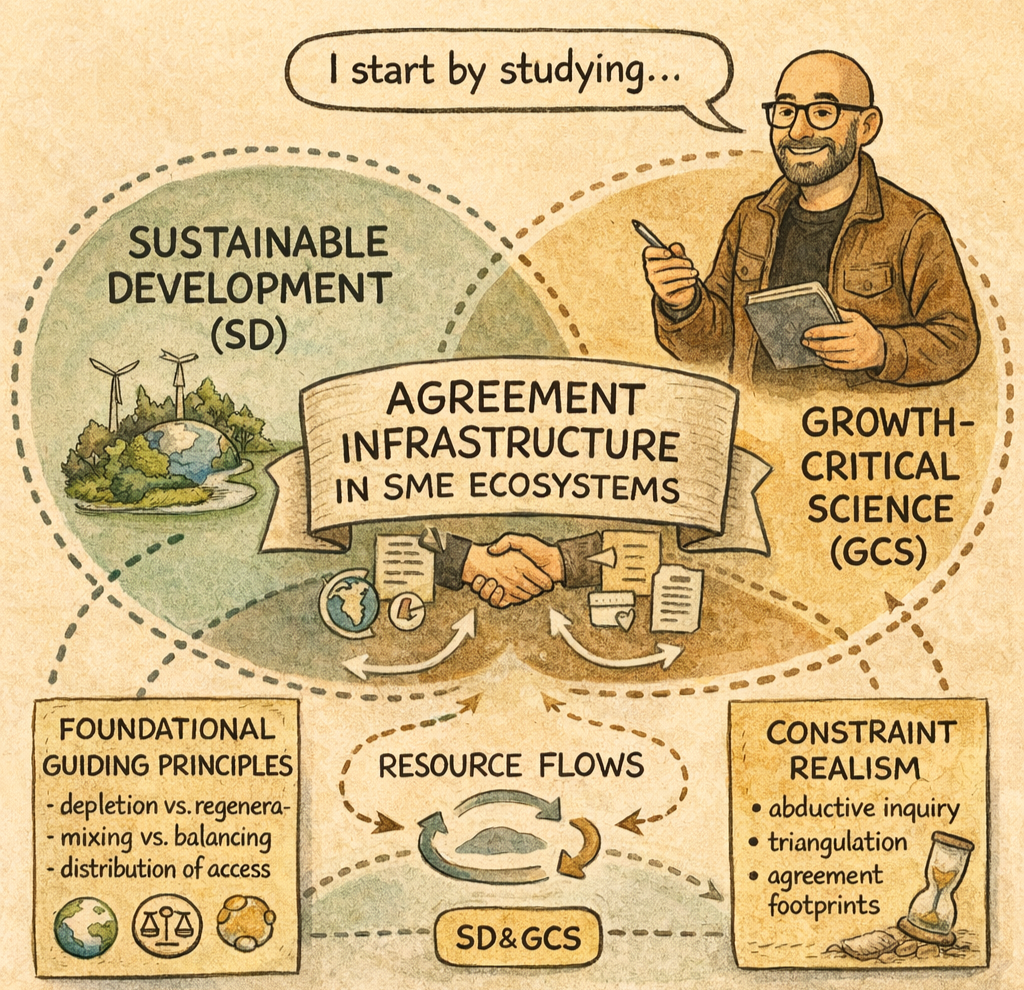

Doing the LUT course on Sustainability and Impact in Business Research, I realized that my research is rooted in both sustainable development (SD) and growth-critical science (GCS), but I don’t start with the question, “Which camp am I in?”

I start with a problem I keep seeing in SMEs: when constraints become real, the first thing that breaks is rarely “strategy.” It’s the agreement structure underlying cooperation, who can decide, how exceptions are handled, what is safe to say, and where costs and risks end up (Hinske, 2025a; Hinske, 2025b). That is the layer I’m trying to make visible and researchable. This layer is present in both SD and GCS. In my earlier assignment, I argued, reflecting on a dialogue between Rees and Hagens (Hagens, 2023), that the economy is not separate from biophysical limits. But in my current PhD work, I’m focusing on what happens to resource flows within organisations and ecosystems when agreements change: interactions either become triple-loop learning-capable or shift costs.

This is why I find the “foundational guiding principles” framing helpful. Hejnowicz and Ritchie-Dunham (2024) aim to make sustainability coherent at the Earth-system level (rates of depletion vs. replenishment, mixing vs. balancing, distribution of access, and limits to growth in volume/consumption). I use them as a discipline against wishful sustainability talk: they make “constraints” non-optional (Hejnowicz & Ritchie-Dunham, 2024).

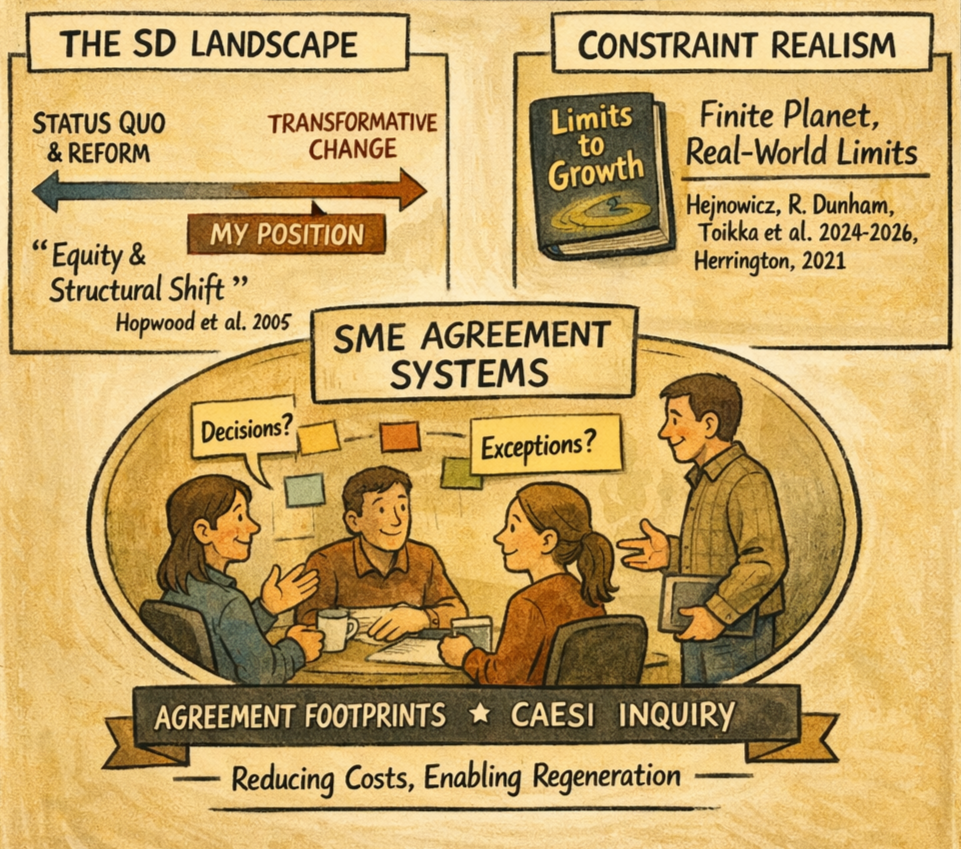

Hopwood et al. (2005) then helped me see my position inside SD. Their map shows that SD is not a single idea; it spans from status quo and reform approaches to more transformative ones, depending on how seriously you take equity and structural change (Hopwood et al., 2005). When I read their map, I recognize why my own work sits closer to the transformative corner: many incremental fixes (KPIs, reporting, efficiency projects) create activity without changing the epistemology (fundamental assumptions and framings). In my own writing, I’ve called this “good strategies failing” because the agreements that actually steer behaviour remain untouched (Hinske, 2025a).

GCS is closely related to my last book, "The Impossibilities of the Circular Economy" (Lehmann et al., 2023). GCS is about realism about constraints. Toikka et al. (2026) describe a shared point: perpetual growth on a finite planet cannot be treated as a neutral baseline (Toikka et al., 2026). Herrington’s update to Limits to Growth sharpened that for me: not because World3 predicts perfectly, but because it challenges the comfort story that we’ll naturally decouple “in time” (Herrington, 2021).

For SMEs, this matters in a very down-to-earth way: under pressure, agreement systems either become renegotiation-capable, or they externalise costs to employees, suppliers, communities, or future viability.

Methodologically, I’m trying to keep my work honest. CAESI is my shorthand: abductive inquiry, triangulation, and practical falsification without turning research into consulting (Hinske, 2025c). In practice, I use short signals (including surveys) as entry points, but I treat “survey ≠ diagnosis” as a strict rule (Hinske, 2025d). The real evidence comes from what I call agreement footprints: observable residues of coordination, recurring escalation loops, unclear decision rights, handoff gaps, and critique that is invited but never integrated (Hinske, 2026). I also refuse recommendations, because advice can replace learning with borrowed certainty. What I try to give back instead are conservative working explanations and small next experiments that can fail safely (Hinske, 2025b).

So my positioning is:

SD as a contested discourse, I locate myself within (Hopwood et al., 2005),

GCS as constraint realism (Lehmann et al., 2023; Toikka et al., 2026; Herrington, 2021; Hejnowicz & Ritchie-Dunham, 2024),

and my empirical niche as agreements-as-infrastructure in SME ecosystems, studied through CAESI and agreement footprints (Hinske, 2025c; Hinske, 2026).

My contribution is modest but concrete: make agreement systems visible enough to compare across cases, and test which agreement patterns reduce cost/risk shifting and increase regenerative capacity under limits.

References

Hagens, N. (2023). William E. Rees: “The fundamental issue – overshoot” | The Great Simplification #53 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQTuDttP2Yg

Hejnowicz, A. P., & Ritchie-Dunham, J. L. (2024). Foundational guiding principles for a flourishing Earth system. Business and Society Review, 129, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12349

Herrington, G. (2021). Update to limits to growth: Comparing the World3 model with empirical data. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 25(3), 614–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13084

Hinske, C. (2025a). Why good strategies fail: The invisible problem of agreements. 360Dialogues (PhD Notes). https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/q3nt3kwyn5eh25mbmcjh99tj0ziyv5

Hinske, C. (2025b). Giving back without consulting: Why I refuse recommendations. 360Dialogues (PhD Notes). https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/giving-back-without-consulting-why-i-refuse-recommendations

Hinske, C. (2025c). 03_Final_Research_Plan_2025_Ecosystem_Flourishing [Research plan]. LUT Doctoral School.

Hinske, C. (2025d). Survey ≠ diagnosis: Using a valid signal without overclaiming it. 360Dialogues. https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/survey-diagnosis-using-a-valid-signal-without-overclaiming-it

Hinske, C. (2026). A 35-minute interview that produces evidence. 360Dialogues (PhD Notes). https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/a-35-minute-interview-that-produces-evidence

Hopwood, B., Mellor, M., & O’Brien, G. (2005). Sustainable development: Mapping different approaches. Sustainable Development, 13(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.244

Lehmann, H., Hinske, C., de Margerie, V., & Slaveikova Nikolova, A. (Eds.). (2023). The impossibilities of the circular economy: Separating aspirations from reality (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003244196

Toikka, A., Ruuska, T., Wiman, L., & Heikkurinen, P. (2026). Degrowth and postgrowth: A systematic literature review of growth-critical science. Ecological Economics, 240, 108830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2025.108830