Survey ≠ Diagnosis: Using a Valid Signal Without Overclaiming It

Note: This text reflects conceptual research thinking. It does not describe or assess any specific organization. Examples and situations referenced are synthetic or composite and are used solely for analytical purposes.

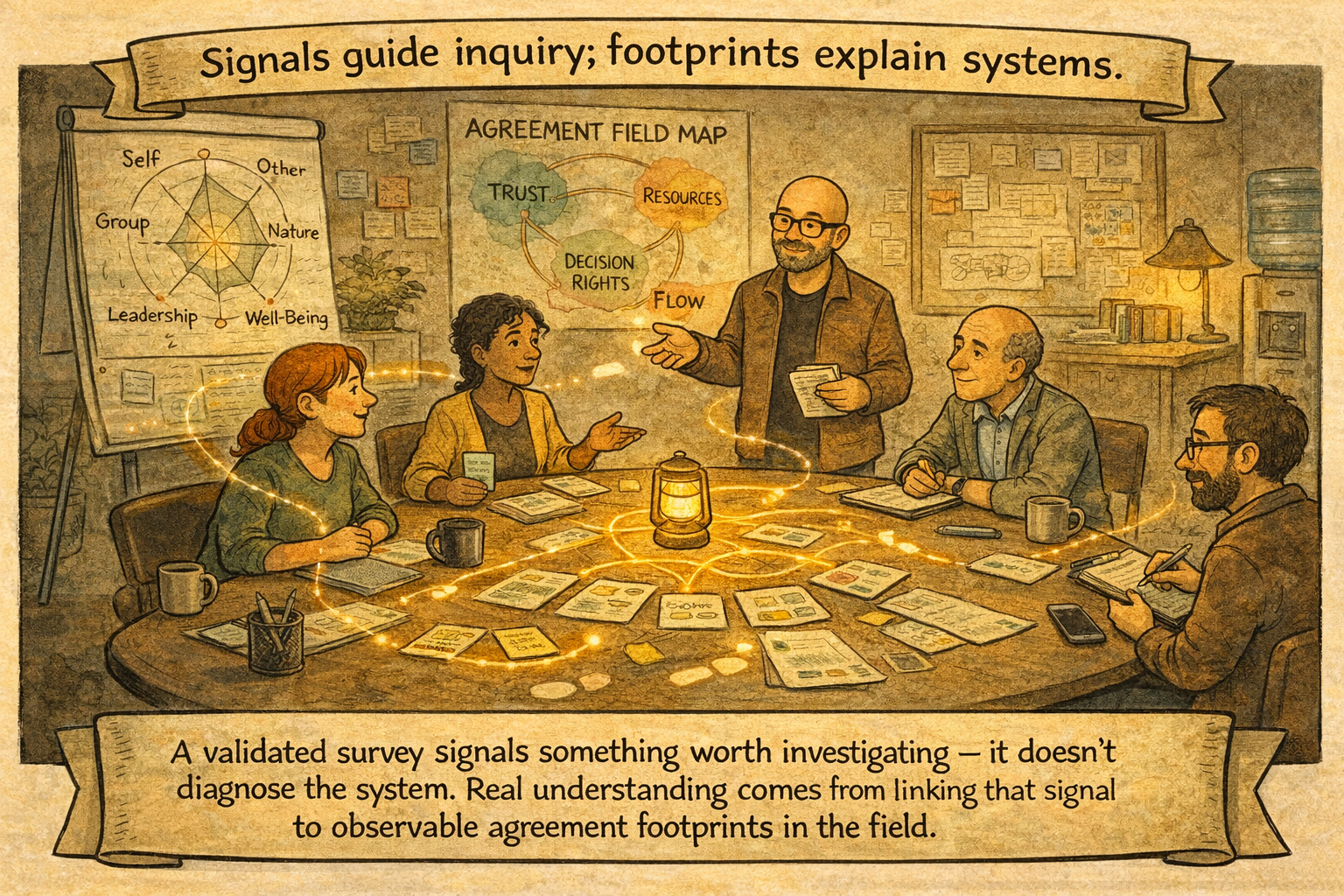

In the last blog, I reflected on the ladder I use to move from a first signal to evidence-backed working explanations: felt experience as the entry point, validation through shadowing, and agreement footprints as the unit of observation. This post zooms in on the first rung of that ladder. Not because the survey is “the method,” but because the most common failure mode occurs there: treating a valid signal as if it were already a diagnosis.

A validated survey can be used in two very different ways. One way is to treat it as a diagnosis and act as if the agreement system has already been understood. The other treats it as what it is best at: a precise indication of where coordination is experienced as workable or unworkable, coherent or friction-heavy. That difference may sound small, but it shapes what happens next. If you treat the signal as a diagnosis, you risk building overconfidence. If you treat it as a starting point, you can turn it into a disciplined inquiry.

What the AHC gives—and what it cannot give

The Agreements Health Check captures felt experience as a yes/no orientation to a person's lived reality. People tend to hear “felt experience” and assume softness, but the point here is not emotion. The point is experience as information: do we experience this area as workable or not, enabling or constraining, coherent or not?

That is strong precisely because it stays close to experience. But it also has a built-in limit. The survey does not show the agreement system itself; it shows the experienced output of an agreement system. Without further inquiry, it cannot tell you which agreements produce the yes/no experience, and it cannot tell you whether the yes/no is stable across roles and situations.

Intersubjectivity is the hinge

A survey result can change meaning depending on who answers it. If only one person answers, the output is not “wrong,” but it is not intersubjective. It is a data point. If multiple people across roles answer, the output becomes something else: a first approximation of shared reality. In SMEs, that distinction matters more than statistical formality, because the goal is not population inference. The goal is role-diverse coverage of lived coordination.

My rule of thumb is simple: I aim for broad representation across levels and roles, with roughly 35% participation. In very small organizations, the target becomes “as close to everyone as feasible.” In larger ones, I prioritize role coverage over raw percentage.

When coverage is thin, I do not hide it. I interpret conservatively and label it as such. I treat thin participation as diagnostic in itself. If multi-voice participation is not considered worth the effort, the agreement-quality question is not salient enough to justify attention and coordination costs. That does not mean the organization is “bad.” It means agreement quality is not currently perceived as relevant enough to spend coordination energy on.

The real danger is overconfidence, not “measurement error”

The instrument isn’t wrong; however, when n is small, the output is better treated as a signal than as an intersubjective description—valid measurement does not remove sampling bias.

The danger isn’t that people “lied.” The danger is that a small sample can lead to a story of “we’re doing fine,” and the group starts making decisions based on it. In one reflection, I used the image of a former competitive athlete in his mid-40s who assumes he can still run a professional marathon. The issue isn’t ambition. The problem is what happens when a self-image prevents a realistic assessment of capacity, recovery time, and risk.

In organizations, the equivalent is treating agreement quality as good enough and therefore unworthy of deeper validation, while the coordination costs show up elsewhere—in downstream fixes, invisible repair work, defensive coordination, or risk displacement.

The validation move: from signal to agreement footprints

When a survey output looks “too good to be true,” my first move is not to debate. It is to build hypotheses. I formulate assumptions that can be tested through shadowing and, when useful, through multi-role interaction.

The reason for field validation is straightforward. I validate whether the felt experience signal matches coordination reality, and I identify which agreements are producing that experience. Practically, that means looking for agreement footprints: tangible and intangible traces that show the experience is rooted in evidence rather than aspiration.

Agreement footprints can be documents, but they can also be interaction residues and coordination traces: who can question what, how exceptions are handled, where repair work accumulates, what gets escalated, what gets tracked or not tracked, and which tensions repeat across roles.

This is also why I am careful with internal documents. Sometimes I deprioritize them because they describe the envisioned result rather than the realized coordination reality. In those cases, I treat documents as claims, use them to locate vocabulary, and then ask for concrete traces and observational confirmation.

Translating agreement quality into performance language

I raise salience without pitching by translating agreement quality into costs, financial risks, and risk ratings. I present these as assumptions based on the provided data—starting points for further conversation and validation—not as final calculations. The point is not fear. The point is legibility: making invisible coordination dynamics discussable in a language SMEs already use for decisions.

A simple test logic helps here. If agreement quality is high, we should observe low friction, fewer downstream fixes, and learning that accumulates rather than resets. If agreement quality is overestimated, we should observe a mismatch between the described experience and the coordination reality. If agreement quality is uneven across roles, we should observe different realities within the same company.

Used this way, the survey does what it does best: it provides an entry signal that structures inquiry. The diagnosis does not happen in the questionnaire. It happens when the signal is confronted with agreement footprints and turned into conservative, testable working explanations.