Why Good Strategies Fail: The Invisible Problem of Agreements

Note: This text reflects conceptual research thinking. It does not describe or assess any specific organization. Examples and situations referenced are synthetic or composite and are used solely for analytical purposes.

Strategy Rarely Changes What People Actually Do

Most organizations do not fail because they lack a good strategy.

They fail despite having one.

Purpose is articulated. Values are posted on the wall. Goals are aligned.

Yet the results do not materialize.

Across my work with organizations, students, and research partners, the same pattern appears again and again: when outcomes disappoint, attention turns to content, new strategies, new priorities, new initiatives. The assumption is that something must be wrong with the plan.

What is rarely examined is what actually governs everyday behavior: the implicit agreements that shape how people make decisions, take risks, avoid exposure, or pass responsibility along.

These agreements are rarely named.

They do not appear in strategy documents.

Yet they determine what happens in practice.

This blog advances a simple, uncomfortable claim:

Organizations do not change through better intentions, but through different agreements.

Why Alignment Rarely Works

“Alignment” has become one of the most overused terms in organizational life. Leadership teams align on strategy. Departments align on objectives. Individuals align on values. Yet alignment often remains cosmetic.

The reason is straightforward: alignment typically operates at the level of language, whereas behavior operates at the level of consequences. People do not act according to what is written or said; they act according to what feels safe, rewarded, or penalized. An organization may declare collaboration as a core value, while implicitly punishing those who expose uncertainty or challenge decisions. It may promote learning while rewarding predictability and control. In such contexts, no amount of alignment workshops will change behavior. This is not a failure of motivation or competence. It is a structural issue. When implicit expectations contradict explicit intentions, the system reliably follows the implicit rules.

As long as organizations treat misalignment as a communication problem rather than a structural issue, their efforts at change will remain superficial.

The Blind Spot: Agreements as System Logic

To understand why strategies fail, it helps to look beneath behavior and focus on the system logic that produces it. That logic is encoded in agreements, both explicit and implicit ones.

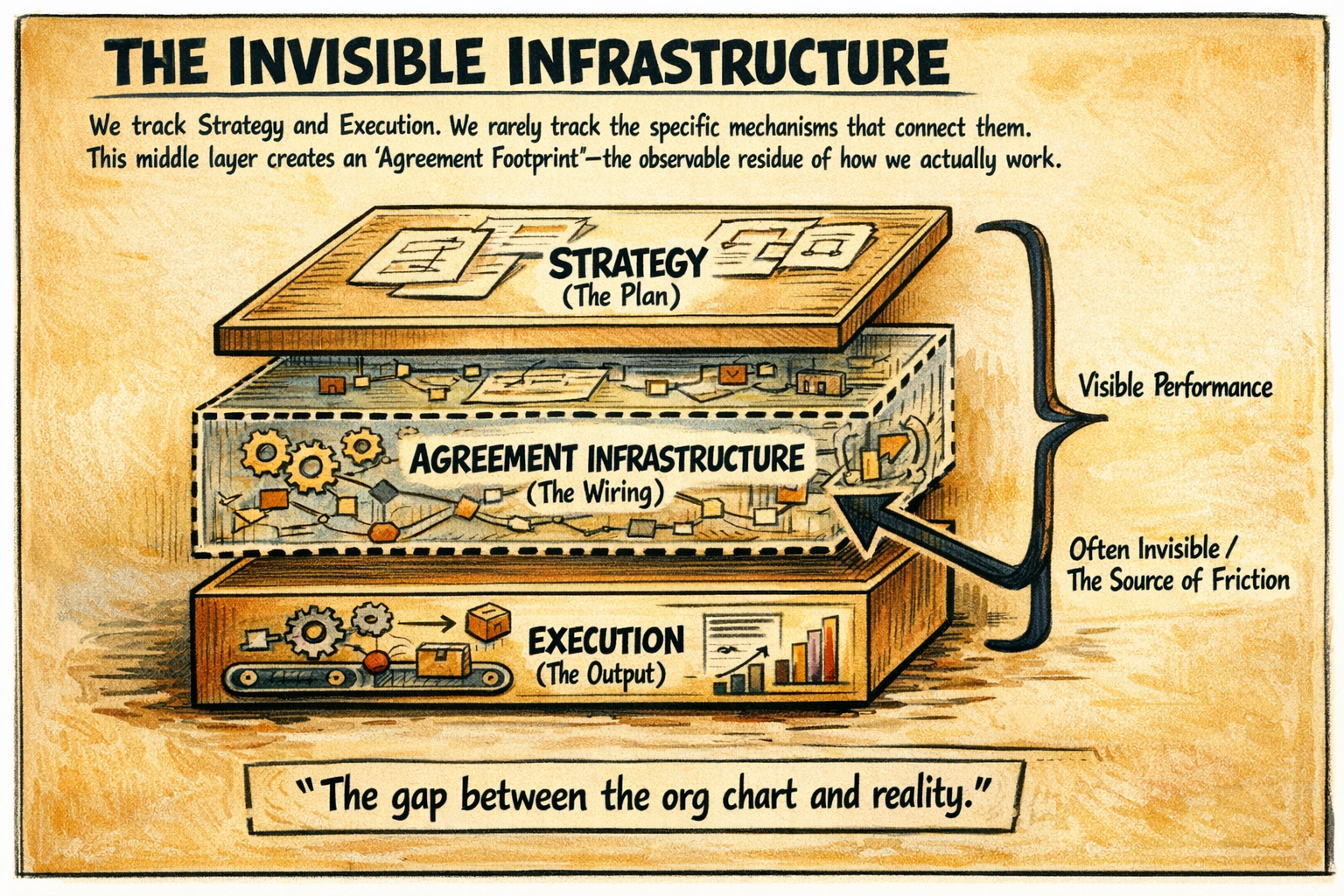

A simple framework makes this visible:

Agreements → Behavior → Outcomes + Experiences

Agreements include formal contracts, targets, and governance mechanisms, but also unspoken norms: what can be questioned, who bears risk, how mistakes are handled, and what success really means. These agreements shape behavior long before individuals consciously reflect on them.

Behavior, in turn, aggregates into patterns: decision routines, risk avoidance, defensive coordination, or genuine collaboration. These patterns then yield outcomes, performance, innovation, trust, and culture.

When outcomes and experiences disappoint, organizations often try to correct behavior directly. But behavior is downstream. If the agreements remain unchanged, behavior will revert, no matter how sincere the effort.

Seen this way, persistent underperformance is not a moral failing. It is a signal that the system’s agreements are misaligned with its aspirations.

Scarcity and Flourishing as Decision Logics

Much of this dynamic can be understood through the contrast between two underlying decision logics: scarcity and flourishing.

Scarcity thinking is not inherently wrong. It prioritizes control, predictability, and risk minimization. It is highly effective in stable environments with clear cause-and-effect relationships.

Flourishing, by contrast, assumes interdependence, learning, and shared responsibility. It accepts uncertainty as a condition of progress and treats relationships as productive assets rather than liabilities.

The problem arises when organizations articulate strategies that require flourishing behavior, initiative, collaboration, and adaptation, while operating on scarcity-based agreements. In such cases, people are asked to act under assumptions that the system does not actually support.

Strategies fail not because people resist change, but because they are expected to behave according to assumptions the system contradicts.

Practical Implications

This perspective has several practical implications.

First, meaningful change begins with diagnosis, not with vision. Before introducing new goals or values, organizations must examine the agreements that currently govern decisions and accountability.

Second, conversations alone are insufficient. Without structural agreements that redistribute risk, authority, and responsibility, dialogue remains performative.

Third, cultural work that ignores agreements becomes symbolic. Posters and principles cannot compensate for systems that reward different behavior.

None of this requires heroism or radical transformation. It requires making the invisible visible and treating agreements as design choices rather than fixed realities.

Why Change Begins With Agreements, Not Motivation

If organizations are serious about change, they must stop trying to motivate people and start making their systems legible. Agreements are not soft factors. They are the infrastructure on which decisions, accountability, and trust rest. As long as this infrastructure remains invisible, organizations will continue to address symptoms, new strategies, new programs, new language, while outcomes remain stubbornly unchanged. Where agreements become visible and negotiable, something more fundamental shifts. People begin to make different decisions without being persuaded or pushed.

Not because they are better people.

But because the system finally allows it.