From Projects to Systems: Designing for Learning at Scale

Note: This text reflects conceptual research thinking. It does not describe or assess any specific organization. Examples and situations referenced are synthetic or composite and are used solely for analytical purposes.

Why Projects Cannot Carry Systemic Change

After diagnosing why strategies fail when agreements remain invisible, a second question follows almost inevitably:

If intentions and motivation are not enough, what actually enables change to endure?

In many organizations, the default answer is the project. New priorities are translated into initiatives, task forces, pilots, or programs. Each comes with a timeline, a budget, and a set of deliverables. When results disappoint, the response is often to launch another project—better scoped, better staffed, more tightly managed.

Yet the underlying pattern rarely shifts.

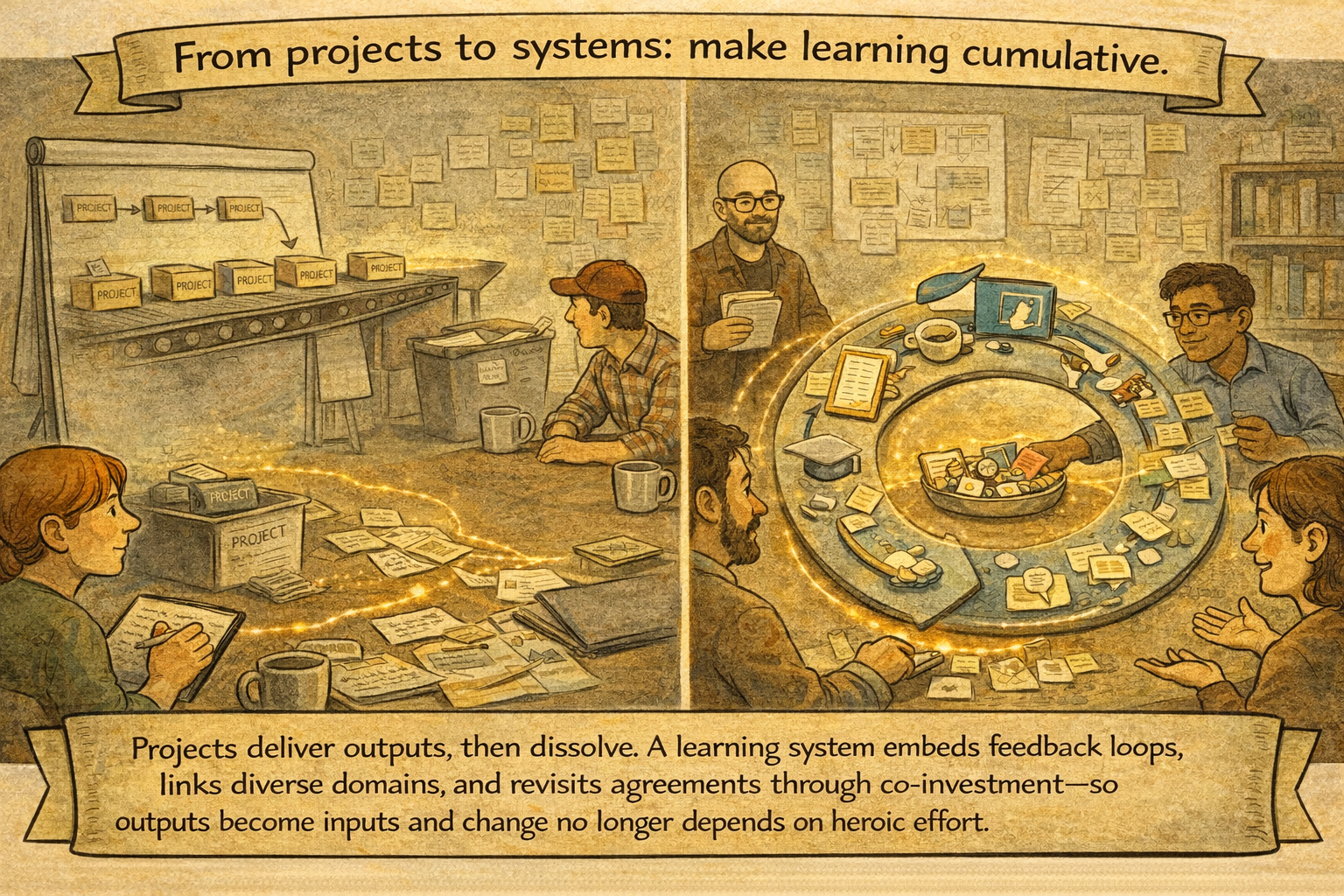

Projects are designed to deliver outputs, not to change systems. They are temporary by nature. They end precisely when learning should begin to compound. Once the project dissolves, behavior returns to its previous equilibrium, governed by the same agreements that existed before.

This is not a failure of execution. It is a mismatch between ambition and structure. Systemic challenges—those involving learning, coordination, and shared responsibility—cannot be addressed by episodic interventions. They require a different form altogether.

What Makes a System Learn

Learning at scale does not happen through isolated insight. It happens through feedback loops that connect action, reflection, and adjustment over time.

A learning system has three defining characteristics:

First, it generates evidence as a by-product of normal activity. Learning is not an add-on; it is embedded in how work is done.

Second, it connects domains that are usually separated—research, education, practice, and communication—so that insight in one domain informs the others.

Third, it revisits its own agreements regularly. Learning systems are reflexive. They not only ask what we are doing but also under what assumptions we are doing it.

When these conditions are absent, learning remains local and fragile. Insights stay trapped in reports, classrooms, or individual experience. When they are present, learning becomes cumulative.

From Pipelines to Flywheels

Most organizational designs still resemble pipelines. Inputs are transformed into outputs through linear stages. Education produces graduates. Research produces publications. Business support produces reports or recommendations. Each domain optimizes for its own performance.

The limitation of pipelines is not inefficiency but isolation. Value flows in one direction, and learning dissipates at the end of the line.

By contrast, a flywheel is circular. Outputs from one domain become inputs for another. Research informs teaching. Teaching generates field data. Field practice feeds back into research. Publishing returns insights to the wider ecosystem, inviting new participation.

In such an architecture, momentum builds through interaction rather than control. The system becomes self-reinforcing. No single intervention carries the burden of change; the structure itself does the work.

This shift—from pipeline to flywheel—is architectural, not cultural. It changes what happens even when individuals rotate or priorities shift.

Co-Investment as a Design Principle

Architecture alone is insufficient without governance that matches its logic.

Traditional project governance relies on transactions: deliverables exchanged for resources. While effective for bounded tasks, this model reinforces scarcity-based agreements—control, compliance, and short-term optimization.

A learning architecture requires a different agreement: co-investment.

In co-investment, partners contribute different forms of capital—knowledge, data, legitimacy, access—toward a shared purpose. Value is not predefined as a deliverable but emerges through interaction. Accountability shifts from output control to mutual reflection: are we still living up to what we agreed to pursue together?

This form of governance does not remove discipline. It replaces compliance with coherence. The system remains aligned not because it is enforced, but because its agreements are revisited explicitly.

What Architecture Changes That Strategy Cannot

Strategies articulate direction. Architecture determines what is possible.

Where architecture is absent, strategy depends on extraordinary effort. Progress requires constant coordination, persuasion, and reinforcement. When attention wanes, the system reverts.

Where architecture is present, behavior shifts without instruction. Learning travels. Responsibility redistributes. People make different decisions because the system supports them in doing so.

This is the critical distinction: strategy sets intention; architecture shapes probability.

Seen this way, many organizational frustrations become intelligible. The issue is not resistance to change, lack of leadership, or insufficient clarity. It is that the system has never been designed to learn in the first place.

Designing for Participation, Not Compliance

Learning architectures do not scale through control. They scale through participation.

Instead of asking who must comply, they ask how different actors can meaningfully enter the system. Participation may take many forms: contributing data, engaging in dialogue, applying insights, or sharing experience publicly. Each mode reinforces the others.

This design choice matters. Compliance creates minimal adherence. Participation creates ownership. When people choose to engage, they internalize responsibility for the system’s success.

Designing for participation does not eliminate hierarchy or expertise. It clarifies roles while keeping boundaries permeable. Authority becomes contextual rather than positional.

When Architecture Does the Heavy Lifting

The implications of all this are both sobering and hopeful.

Sobering, because no amount of motivation can compensate for poor design. Hopeful, because well-designed systems reduce the need for heroic leadership.

When agreements are explicit, feedback loops are active, and participation is built into the structure, learning becomes durable. Change no longer depends on extraordinary individuals or constant pressure. It becomes a property of the system itself.

This is where the focus shifts again—not to better strategy or architecture, but to the stance required to work within such systems.

That question—how leadership changes when control gives way to stewardship—is the subject of the next essay.