Different Banking Portfolios, One Gap: Turning “Agreement Footprints” Into Usable Evidence

Short on time? Open the sections below.

-

Most credit workflows are strong in financial legibility but seem weak in coordination legibility. This note explores how “agreement footprints” can turn coordination dynamics into inspectable, decision-grade evidence.

-

Many SME credit events start as coordination failure (e.g. dependencies, unclear decision rights, unmanaged exceptions) long before the financials deteriorate. Agreement footprints help spot early warning signals before they become disputes, delays, cash stress, or credit events.

-

Decision rights: who decides what, especially under exceptions

Escalation: how issues get handled when pressure rises

Dependencies: where work stalls because “we can’t move without X”

Learning loops: whether problems get fixed or keep returning

Negotiability: whether agreements can be questioned without punishment

Execution under stress: whether coordination holds under pressure

-

This is a PhD note shared for learning, not a pitch. It is not a culture audit or maturity model. It offers a practical way to translate “soft” coordination signals into evidence that can be cross-checked inside credit routines.

-

Why I keep ending up at agreements when talking about risk: Hinske (2026).

The initial working hypothesis I stress-tested with practitioners: Hinske (2025b).

How I translate agreement quality into financial risk language conservatively (without pretending to be more precise than the evidence allows): Hinske (2025c).

Banking practice is designed to make defensible decisions: repeatable across cases, explainable to colleagues, and robust under scrutiny. That discipline is a feature, not a bug.

At the same time, a recurring tension keeps surfacing at the boundary between SMEs and banks. Some firms find that the risk-prevention measures they take and how they coordinate work within and across their business ecosystem don’t easily become legible within standard credit workflows (Hinske, 2022; Ritchie-Dunham, 2026). In earlier notes, I’ve described this as a recurring pattern in “risk work”: the moment you try to be concrete about risk, you keep getting pushed back toward agreements, decision rights, handovers, escalation norms, what is safe to surface, and how learning loops are embedded (Hinske, 2026).

This PhD Note is a reflection about the next step in that logic: what it would take to turn agreement dynamics into usable evidence, without naïveté, without theater, and without fake precision.

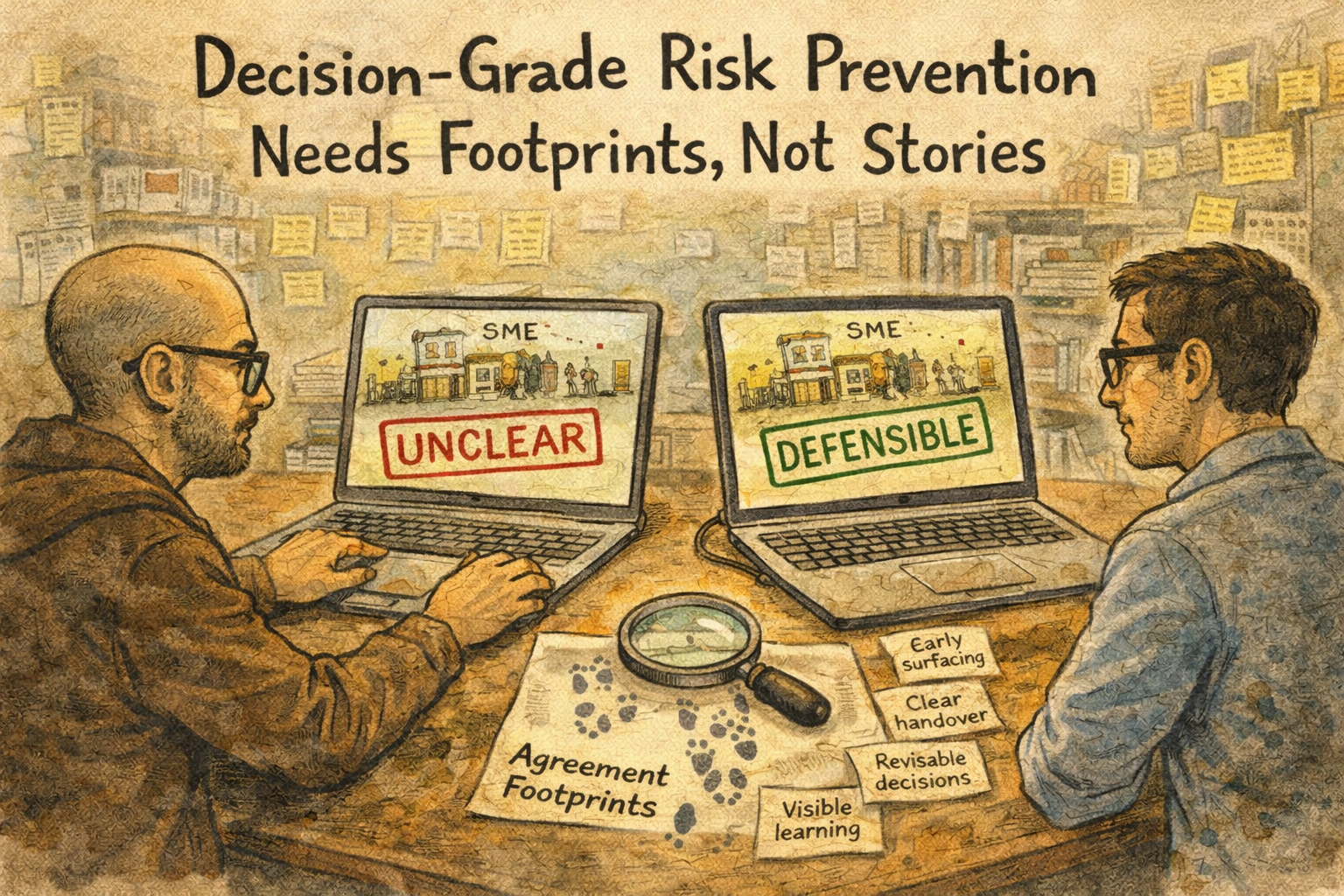

Risk prevention needs footprints, not theater: decision workflows can only use what becomes repeatable, explainable, and robust under scrutiny.

The gap, stated cleanly.

Here is the gap as I currently understand it:

Field signal from banking practice (composite). In several conversations, bankers immediately recognized the gap. They shared a recurring pattern they had seen across cases: an SME grows steadily for years, then a generation decides to sell, and shortly after the sale, the firm’s value collapses. They never used this as a moral story about families or founders. They pointed to a risk-relevant factor that often emerges after a major ownership shift but is hard to capture early in standard workflows. What made the observation sharper is his next point. As the human interface across the banking landscape has been reduced (banking staff are less often present 1:1 with smaller firms), banks lose a critical sensing channel, the human. The result is weaker early visibility into agreement dynamics that later determine whether a growing firm remains resilient once the context changes.

There is no reliable, shared process, and no reliable measurement tool, that makes agreement quality in a social system legible as decision-grade risk prevention.

This is not a “banks don’t care” claim. It’s not an “SMEs are right” claim either. It’s a systems-and-measurement claim: even when experienced practitioners recognize that “something non-financial matters here,” the system often lacks a consistent way to capture it, test it, and use it across cases without drifting into storytelling.

Three conceptual anchors help me keep this grounded, plus one empirical proof-point from banking research:

Organizations operate in ecosystems. Resilience and failure are not only “inside the firm”; they are shaped by coordination patterns across customers, suppliers, partners, and institutions (Ritchie-Dunham, Dinwoodie, & Maczko, 2025; Ritchie-Dunham & Dinwoodie, 2023).

Measurement is disciplined, collaborative sensemaking. It is not “objective capture.” It is the joint construction of proxies that are good enough for a specific purpose, iterated through use, without pretending to have perfect precision (Aguilera, 2025).

This is measurable in banking settings, at scale, when “agreements” are treated as an explicit measurement object. A large microfinance bank study operationalizes culture partly through agreement structures (and observable “symbolic acts”), and includes an agreement’s health measure alongside flourishing and other outcomes, with a longitudinal, multi-wave design and extensive samples (Ritchie-Dunham et al., 2024).

So the practical question becomes: what would a bank need to see, reliably and consistently, to treat agreement-based risk prevention as inspectable evidence rather than as narrative?

Agreements as coordination infrastructure, not soft talk

In this post, I use the term 'agreements' in a precise, operational sense: agreements are the social and organizational infrastructure that enable coordinated action across roles and boundaries. They are not the same as “nice relationships,” and they are not reducible to written policies. In banking research and practice-oriented scholarship, agreements appear as structures and routines. They are observable commitments, boundary-setting moves, and symbolic acts that stabilize cooperation and shape what people actually do (Ritchie-Dunham et al., 2024).

That aligns with how I use the term in my own work: agreements are where coordination becomes concrete, who can decide, how handovers work, what gets escalated, what is safe to surface early, how exceptions are handled, or whether learning loops are real (Hinske, 2026; Hinske, 2025b). Because agreements are enacted, they leave traces in practice.

In other words, the question is not whether agreements matter, but which agreement footprints can be made reliably inspectable for a given decision purpose.

Which leads to the concept I want to sharpen here:

Agreement footprints as the measurement bridge

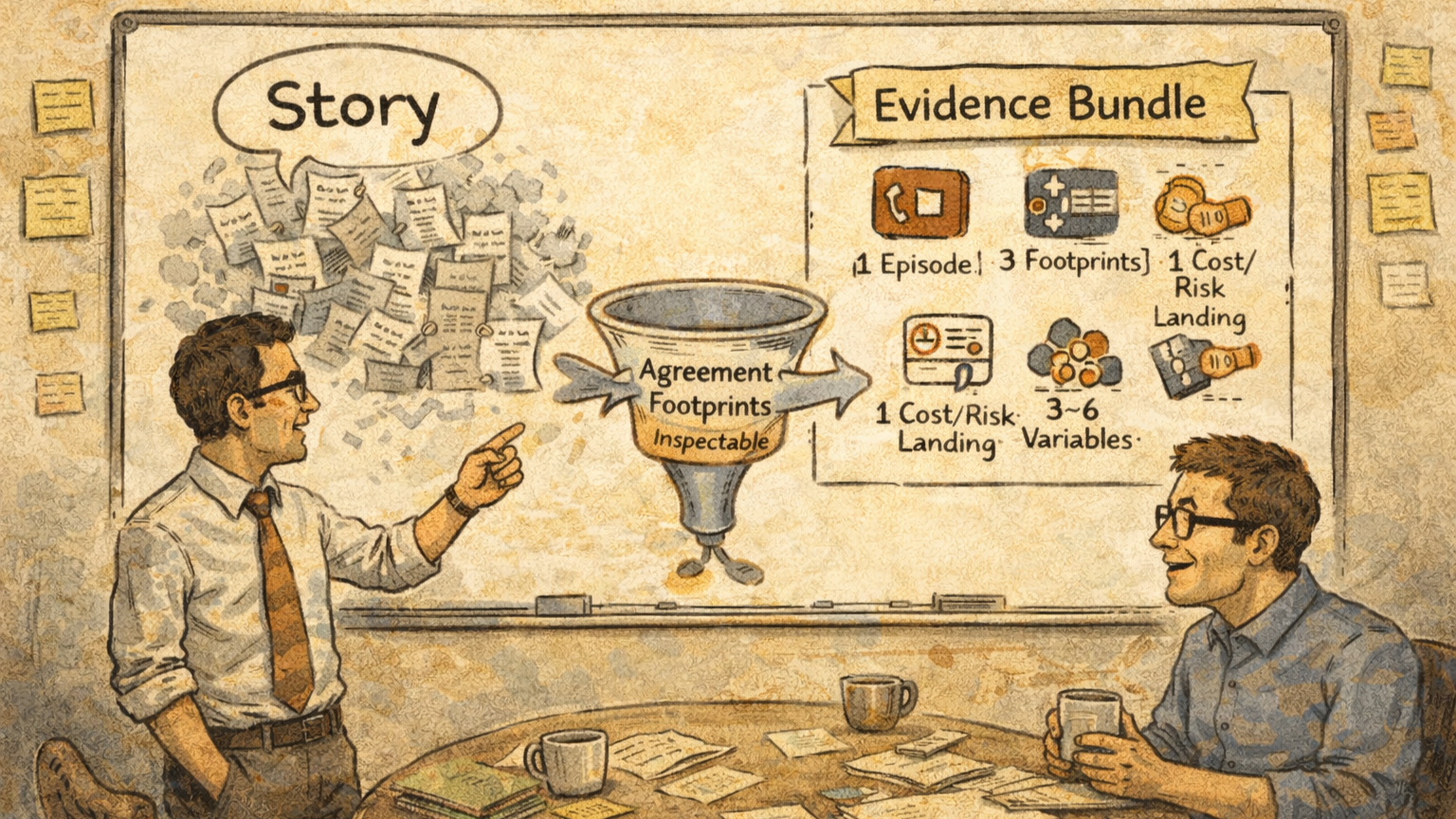

From stories to decision-grade signals: agreement footprints act as a filter that produces a minimal evidence bundle (episode, footprints, cost/risk landing, variables).

In the three posts linked above, I did three things: I treated a recurring SME claim as a hypothesis to stress-test (Hinske, 2025b), I translated “agreement quality” into conservative risk language without pretending to have decision-grade precision yet (Hinske, 2025c), and I clarified why risk conversations keep pushing me back toward agreements as the operative coordination layer (Hinske, 2026). This note takes the next step: what would count as evidence, in a form that is repeatable across cases, explainable to colleagues, and robust under scrutiny.

That is where the idea of agreement footprints comes in. Instead of asking anyone to “believe” agreement narratives, footprints specify what can be checked: small, observable residues of how coordination is actually structured, traces that remain visible in day-to-day work even when nobody is “talking about agreements.” Footprints are not a moral badge and not a claim of superiority; they are inspectable signals that a coordination routine exists (or does not), and that it is being used (or not).

Footprint families (illustrative, not exhaustive)

Visibility & negotiability footprints

Is there a routine for surfacing tensions early? Is disagreement allowed before it becomes failure? Are decisions revisable when new information appears?Decision-rights & handover footprints

When work crosses boundaries, is it clear who owns what? Do handovers include shared definitions of “done”? Are exceptions handled through routines, or through heroics?Learning-loop footprints

When something goes wrong (or nearly goes wrong), does the system update itself? Do insights carry forward into the next cycle in a way that is visible across roles?Interface footprints across the ecosystem

When customer, supplier, and internal constraints collide, does the system have a way to renegotiate commitments without hiding problems or exporting risk downstream?

What matters here is not whether any single footprint exists, but whether a small set can be co-defined that is:

observable in practice (not only in documents),

non-trivial to fake (or at least not cheap to fake),

plausibly connected to risk-relevant outcomes (surprises, rework, stalled handovers, margin leakage, cash stress).

That is the bridge from “good story” to usable evidence.

Making it decision-grade without turning it into theater

Once a gap is confirmed as “real,” the understandable reflex is to jump straight to a scoring model. I want to resist that reflex, not because models are bad, but because premature scoring is where theater and false precision often enter.

A decision-grade measurement layer is not primarily a model. It is a process discipline that makes evidence usable across cases:

Define intention and use-case clearly.

What decision is the evidence meant to support, and what decisions is it explicitly not meant to support? This is the first guardrail against overreach (Aguilera, 2025).Co-define candidate footprints.

Not a long list. A minimal set that can be checked consistently and that matches actual workflow realities, so “agreement footprints” become inspectable rather than rhetorical.Specify evidence channels.

What counts as seeing a footprint? Which sources are acceptable? What is out of scope by design? This is where you prevent document-theater and “proof by narrative.”Stress-test for false precision and gaming.

If a footprint becomes easy to game, it stops being evidence and becomes performance. The measurement design must include that risk from day one, especially in high-stakes decision-making environments (Hinske, 2025c).Iterate and tighten language.

The goal is not “capturing reality.” The goal is to build a shared, defensible proxy language that improves decision-making while staying honest about limits and uncertainty (Aguilera, 2025).

This is why I keep calling the gap a measurement gap: the missing layer is not motivation or morality. It is legibility, a repeatable way to translate coordination reality into evidence that can survive scrutiny.

What this is, and is not.

To keep the stance academically clean, this is not an attempt to redesign credit policy, sell consulting products, or claim causal effects beyond what data can support (Hinske, 2025b). At this stage, the work is a research move: making a phenomenon measurable enough to test, refine, and use responsibly.

What a “successful next step” looks like now, and why it matters for my PhD

This is the PhD-relevant hinge: my earlier posts established the claim (legibility gap), the translation stance (conservative, no fake precision), and why risk keeps pointing back to agreements (Hinske, 2025b; Hinske, 2025c; Hinske, 2026). What is still missing, scientifically, is a testable, repeatable measurement-and-routing prototype that demonstrates how agreement footprints can become decision-grade evidence in a banking workflow without becoming theater (Aguilera, 2025).

So the next step is not “more talking.” It is an applied rapid research prototype that lets me study (and document) the measurement problem in real conditions, similar in spirit to the staged, low-admin “start in the real system, learn fast, scale later” logic I use on the SME side, but mirrored for banks (Hinske, 2025a).

Concretely, a successful next step should capture three things:

(1) what is already recognizable in practice, (2) where current practice hits a legibility boundary, and (3) what would need to become measurable to move from “recognizable” to “usable.” (Aguilera, 2025; Hinske, 2025b).

From there, I might want to draft a 1–2 page applied rapid research prototype (not a consulting plan) that is deliberately bounded:

Purpose & decision-use: one clear decision-use case (and explicit non-goals), so we don’t overclaim or accidentally design a shadow scoring model (Aguilera, 2025; Hinske, 2025c).

Startpoints in the real workflow: 2–3 portfolio contexts as first “applications” (not a pilot), chosen for learning value and comparability.

Minimal evidence package: a small set of candidate agreement footprints + clearly defined evidence channels (what counts, what does not, what is out of scope), to prevent document-theater and keep privacy boundaries intact (Aguilera, 2025; Hinske, 2025c).

Two measurement moments: a baseline capture and a follow-up after a few months, not to prove causality, but to test stability, interpretability, and operational usability of the footprints language over time.

Joint interpretation step: one structured sensemaking workshop with practitioners to test whether the proxies actually improve decision clarity and whether they produce unwanted gaming incentives (Aguilera, 2025).

Outputs that are immediately usable: (a) a short cross-case “legibility map” (what becomes inspectable, what remains ambiguous), and (b) a concrete, iterated “footprints protocol” that can be routed internally for scaling decisions, without claiming predictive validity prematurely (Hinske, 2025c; Ritchie-Dunham et al., 2025).

If this works, the PhD becomes sharper, not broader: I’m no longer only arguing that agreement dynamics matter, I’m documenting how collaborative measurement can make agreement footprints decision-grade in a high-scrutiny environment (Aguilera, 2025; Hinske, 2025c). And that is exactly the research contribution I want this banking corridor to produce.

References

Aguilera, H. (2025). Collaborative measurement of flourishing. In J. L. Ritchie-Dunham, K. E. Granville-Chapman, & M. T. Lee (Eds.), Leadership for flourishing. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/9780197766101.003.0014

Hinske, C. (2025a). ZDH Wirkungsmessung: Gesprächsgrundlage (Unpublished project concept note).

Hinske, C. (2025b). A working hypothesis to test with a bank: When “low-risk” SMEs feel unseen, and how I plan to stress-test the claim. 360Dialogues (PhD Notes). https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/8183oxdr902a2eekzurblcq8ujjwly

Hinske, C. (2025c). From agreement quality to financial risk: Conservative translation without fake precision. 360Dialogues (PhD Notes). https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/from-agreement-quality-to-financial-risk-conservative-translation-without-fake-precision

Hinske, C. (2026). Risk work keeps pointing me back to agreements. 360Dialogues (PhD Notes). https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/risk-work-keeps-pointing-me-back-to-agreements

Ritchie-Dunham, J. L., & Dinwoodie, D. L. (2023). Leading towards a healthy ecosystem. Developing Leaders Quarterly, (41), 72–87. https://developingleadersquarterly.com/leading-towards-a-healthy-ecosystem/

Ritchie-Dunham, J. L., Chaney Jones, S., Flett, J., Granville-Chapman, K., Pettey, A., Vossler, H., & Lee, M. T. (2024). Love in action: Agreements in a large microfinance bank that scale ecosystem-wide flourishing, organizational impact, and total value generated. Humanistic Management Journal, 9, 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41463-024-00182-y

Ritchie-Dunham, J. L., Dinwoodie, D., & Maczko, K. (2025). Organizational ecosystems of flourishing. In J. L. Ritchie-Dunham, K. E. Granville-Chapman, & M. T. Lee (Eds.), Leadership for flourishing. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/9780197766101.003.0009

Ritchie-Dunham, J. (2026). The CEO’s stuck dashboard: Managing the agreements field when purpose, ESG, and performance don’t line up. Reflections of a Pactoecographer. https://jimritchiedunham.wordpress.com/2026/01/26/the-ceos-stuck-dashboard-managing-the-agreements-field-when-purpose-esg-and-performance-dont-line-up/

Context note: This post presents conceptual reflections on research. It does not describe, assess, or report on any specific organization. All examples are synthetic or composite and non-attributable. In this note, I reflect on how agreement dynamics shape risk in SME ecosystems. I’m not selling a product or pitching a method, I’m sharing a practical way to make hard-to-detect signals inspectable in credit and risk work.