From Agreement Quality to Financial Risk: Conservative Translation Without Fake Precision

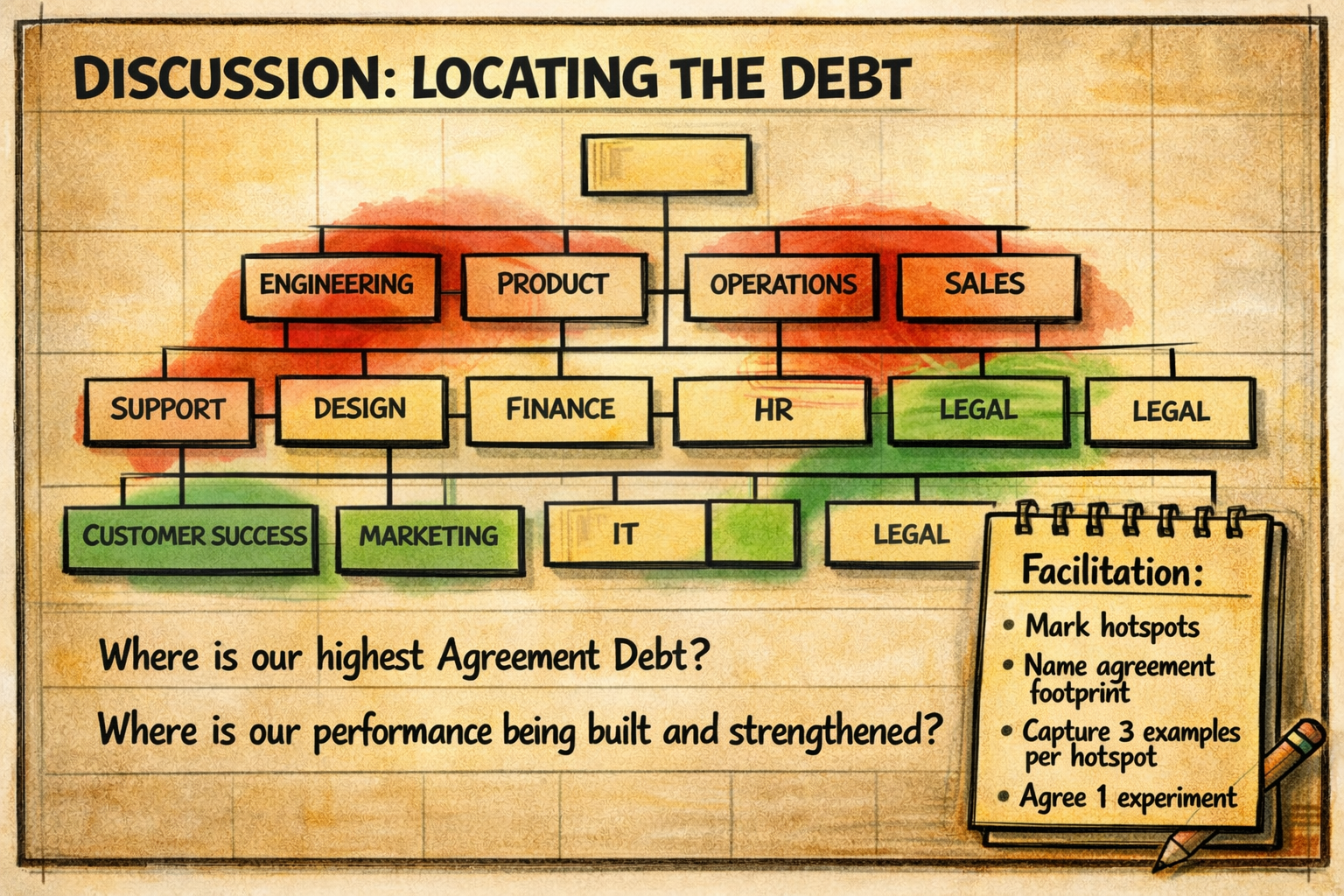

Figure 1. Locating Agreement Debt and Performance Capacity in the Org Chart: A facilitation map that makes coordination patterns discussable without pretending to diagnose. Red zones indicate areas where agreement debt may be accumulating through unclear decision rights, compensation work, or recurring friction. Green zones indicate where agreements appear to build flow, strengthen coordination, and reduce risk exposure. The purpose is not classification but inquiry: to surface agreement footprints, translate them conservatively into cost and risk proxies, and identify one testable experiment.

In earlier posts, I argued that a survey is a signal, not a diagnosis; that field validation occurs through agreement footprints; and that applied research delivers through evidence-backed working explanations and testable experiments, not recommendations. This post sits between those pieces. It shows how I translate agreement quality into financial risk language in a way that is useful for SMEs while staying honest about uncertainty and avoiding consultant theater.

Cost and risk are different, and they compound

Cost is anything that slows down the group/system/SME in achieving its shared purpose while making the journey toward that purpose more resource-intensive. Risk is anything that increases the likelihood that the SME will lose, miss, break, or delay under uncertainty.

Agreement systems shape coordination. Coordination shapes cost. And cost under uncertainty becomes risk. The hard part is not the logic; the hard part is translating it without producing false precision that corners entrepreneurs or inflates certainty.

My stance is simple: translate conservatively, label assumptions as such, and use numbers to open inquiry—not to close it.

A practical pattern: two coordination modes

In the field, I repeatedly see SMEs clustering into two broad coordination modes.

One mode is “reactive.” The organization is busy, talented people are stretched, and exceptions, firefighting, and downstream fixes dominate coordination. The other mode is “anticipatory.” It is not perfect, but agreements are more transparent, issues surface earlier, learning accumulates, and the system wastes less energy compensating for itself.

The point is not to classify firms. The point is to make a question discussable: what proportion of our time and energy is spent on value creation, and what proportion is spent on coordination compensation?

That proportion directly links agreement quality to financial risk.

Conservative translation: start with proxies, not grand models

I do not begin with a full “ROI of agreements” model. I start with conservative proxy buckets that SMEs already recognize, because they are close to lived experience and often supported by traces. A pragmatic move is to begin with a conservative floor, an “underestimate that is still material”, and then refine it through validation. The goal is not an exact number. The goal is a shared, testable working explanation that can guide the following experiment.

Here are three anchor buckets that consistently show up as agreement footprints and are financially legible without stretching the data.

1) Coordination overhead: the hidden tax

Coordination overhead is the energy spent aligning, clarifying, rerouting, escalating, compensating, and repairing, work that arises because agreements are unclear, unsafe, or unnegotiable.

I’ve observed coordination overhead differences of up to ~25% between organizations with different agreement-system quality. I treat that as a field-observed pattern to explore with the company, not as a statistically generalizable benchmark. I use it to show what might be possible, not to drive entrepreneurs into a corner with numbers.

When agreement quality is high, overhead drops because fewer cycles are spent protecting, guessing, or compensating. When agreement quality is low, the tax appears everywhere: meetings multiply, context gets re-explained, approvals bounce, people work around the system, and “just getting it done” becomes the normal mode.

If you want a conservative cost proxy, coordination overhead is usually the first place to look, because it is both pervasive and surprisingly measurable once you stop treating it as “just how work is.”

2) Decision latency: slow flow and expensive fixes

Decision latency shows up as stakeholders complaining about missing information, bottlenecks, or slow processes. That complaint is rarely about impatience. It’s a footprint of unclear decision rights, unclear information agreements, or unspoken risk dynamics that make decisions feel unsafe.

Decision latency is financially relevant for two reasons. First, it delays value: sales, delivery, and investment cycles become longer. Second, it increases repair: when clarity is missing, action happens anyway, and downstream fixes accumulate. Under uncertainty, delayed decisions don’t just cost time; they increase the probability of missing windows, losing customers, and overpaying for urgency.

In other words, slow decisions are not only “inefficient.” They are a signal of an agreement system that can be translated into both cost and risk.

3) Talent drain: exiting objectifying agreement fields

Talent doesn’t leave a job it applied for because it dislikes what it does; it leaves because it is treated like an object, not a subject.

In agreement terms, “being treated like objects” shows up as a de facto field where reality is risky to surface, critique is punished, and “we know better” replaces genuine engagement. People then protect themselves, submit, or leave.

This mechanism plays out across three connected arenas.

With employees, it shows up as systems that treat humans as execution capacity rather than as sensing and learning participants. With customers and partners, it shows up as assuming you know better than the recipient and therefore not engaging strategically with their context. Internally, it shows up as energy spent fighting dynamics that people cannot influence and workarounds that keep the machine running while draining people.

Talent drain is therefore not an HR side topic. It is a coordination and agreement topic with a clear financial tail: hiring costs, onboarding costs, lost capacity, reputational effects, and quality instability.

A note on “percentages” and why I still use them

Numbers are helpful when they clarify reality and dangerous when they pretend to replace it. That is why I use conservative estimates to structure dialogue and validation, not to pressure decision-makers.

The discipline is this: if agreement footprints cannot support the number, it remains a hypothesis. If it can be supported, it becomes a working assumption for testing. The output is not specific. The output is a next-best question that the organization can own.

What this makes possible

Once agreement quality can be discussed in financial language without distortion, a different kind of action becomes possible. Instead of launching belief-based initiatives, the organization can design a small experiment that targets a specific agreement pattern, then observe whether coordination overhead, decision latency, or talent dynamics shift.

That is the bridge I care about: translating agreements into risk without cheap consultancy, and turning risk talk into testable learning rather than control theater.

Note: This text reflects conceptual research thinking. It does not describe or assess any specific organization. Examples and situations referenced are synthetic or composite and are used solely for analytical purposes.