From Diagnosis to Stakeholder Play: Using a Card Deck to Make Agreement Systems Shareable

In earlier posts, I built a sequence: why strategies fail when agreements stay invisible, why projects cannot carry systemic change when learning is not designed into the system, and why control breaks down when value emerges through interaction rather than execution. Then I moved to method: the ladder from felt experience to agreement footprints, the distinction between survey signal and diagnosis, the refusal to give recommendations, and the translation of agreement quality into financial risk language.

This post adds the next practical move: how insights leave the analyst’s head and enter the stakeholder field without turning into a consulting product.

It starts with a request I hear often: “Can we gamify this and use it with our ecosystem?” The intention behind that request is usually sound. SMEs don’t need another report. They need a way to coordinate differently with suppliers, customers, banks, partners, and internal teams. But the word “gamification” is risky because it invites the wrong optimization: optimize the score, protect face, hide the truth.

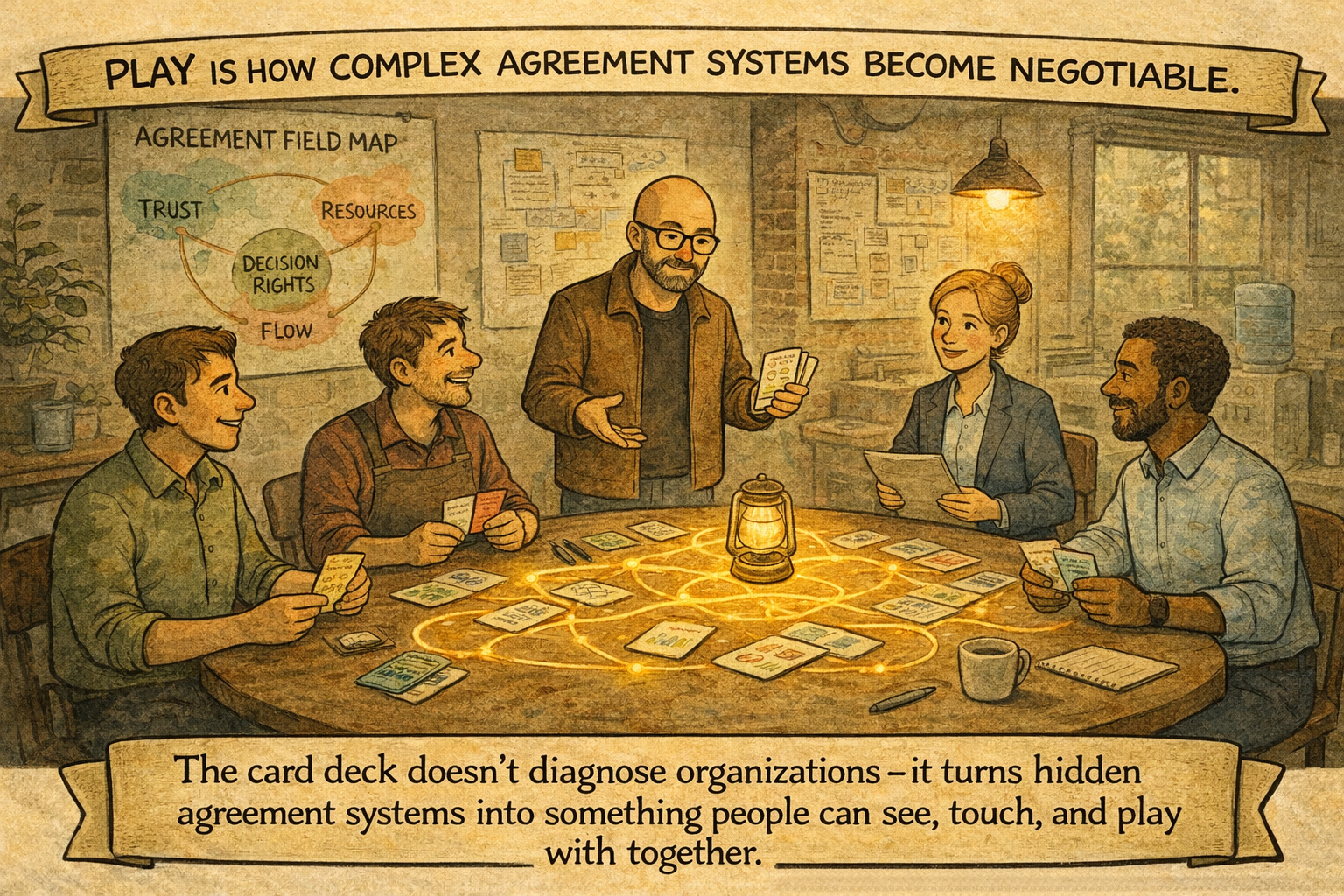

So the question becomes: How do you make agreement systems shareable in a way that increases truth-seeking and agency rather than performance theater?

Why “play” matters, and why “scoring” doesn’t

Play lowers the social cost of speaking. When people can point to a card rather than accuse a person, the system becomes discussable. Scoring tends to undermine that benefit. Once a group believes there is a “right answer,” the conversation shifts from inquiry to impression management.

The deck is not designed to produce a number. It is designed to deliver a shared object of attention that allows multiple roles—and external stakeholders—to work on the same reality without collapsing into opinion battles.

The non-negotiable design rule

The deck exists to prevent one specific collapse: turning a working explanation into a recommendation.

Each card requires four fields that keep the conversation disciplined: a concrete claim about coordination reality, evidence in the form of agreement footprints, the implied cost/risk logic under uncertainty, and a micro-experiment—the smallest test that could reduce uncertainty.

If a group can “finish” a card without footprints and without a test, the card is not doing its job.

Why a small set of cards is stronger than the full deck

Most facilitation failures stem from abundance. Too many prompts, too many dimensions, too many concepts. People lose the thread, and the deck turns into a creative brainstorming session.

In my practice, I start with a deliberately small core set. The internal cross-references then do the real work: once a group has a few strong footholds, they can follow the links and discover how tightly woven the system is. That is not a side feature. It is the point: showing interdependence without forcing abstract systems talk.

The core set I start with (10 cards)

Whether in a quarterly review, a 90-minute workshop, or a 1:1 session, I typically start with the following ten cards. They surface agreement systems quickly, scale to ecosystem settings, and reliably produce testable hypotheses rather than vague reflections:

Card #1 — Decision rights and legitimacy: who decides, and how does that decision become legitimate across the field?

Card #2 — Reliance agreements: which agreements do we rely on without naming them?

Card #3 — Assumed expectations: which unspoken expectations keep creating friction and repair work?

Card #5 — Who gets seen/forgotten: who counts in decisions, and who is systematically missing from the picture?

Card #6 — Where we get stuck: which recurring bottlenecks point to stable agreement patterns?

Card #9 — Avoided topics: what do we avoid talking about even though it shapes outcomes?

Card #13 — Boundaries and handoffs: where do responsibilities evaporate at interfaces—internally or with partners?

Card #17 — Misalignments: where do goals, incentives, or success criteria clash across roles or stakeholders?

Card #19 — Capacity bottlenecks: where does capacity get trapped—and remembered as “normal”?

Card #20 — Market feedback: what does the market signal that we systematically translate poorly (customers/partners/banks)?

Those ten cards are enough to identify and name agreement systems without turning the session into a mapping exercise. They also help stakeholders show up naturally: once decisions, handoffs, missing voices, and market feedback become explicit, the ecosystem becomes visible as a coordination reality, not as a conceptual map.

A canonical session flow that works across formats

The backbone remains stable across settings; only the timeboxing changes.

First, we establish the stakeholder field. If the company wants to use the deck with the ecosystem, the deck must help identify the ecosystem in a way that feels workable. The cards do this indirectly: stakeholders become apparent as soon as the group clarifies who decides, who is missing, where handoffs break, and which feedback gets ignored.

Second, we surface agreement footprints. The deck forces the group to attach footprints to claims, so the conversation moves from “we think” to “we can point to.” Documents matter sometimes, but so do interaction residues and coordination traces.

Third, we formulate hypotheses. This is where reflection becomes design: If this agreement system is operating, we should observe… or If this assumption is false, we should see… The cards help because they keep claims specific and anchored.

Fourth, we design micro-experiments. The deck forces smallness. Not a program. Not a transformation initiative. A micro-adjustment that can be hosted by a named person and observed within a short cycle.

The minimal output is always the same: three hypotheses, three micro-experiments, and an evidence list, with responsible hosts who micro-adjust and accompany the tests so they actually happen.

Why this is a “give back” move, not an implementation move

I don’t use the deck to roll out change. I use it to help a system test its beliefs about itself.

That is why it fits the stance from Blog 6: it provides a structure for truth-seeking without collapsing into advice. It also fits the stance from Blog 7: translating agreement quality into cost and risk language becomes practical when experiments are designed to reduce uncertainty rather than to confirm a narrative.

In that sense, the deck is not an add-on. It is a method bridge. It turns diagnosis into shared learning capacity. It makes agreement systems discussable in the stakeholder field. It does so in a way that is playful enough to lower defensiveness but strict enough to demand evidence and testing.

The tell that the deck is working

When the deck works, three shifts become visible. People stop arguing over interpretations and start comparing evidence. The system stops chasing comprehensive solutions and starts designing small tests. And the conversation stops circling within the company: missing stakeholders are named, interfaces become explicit, and value exchange becomes discussable as a coordination reality rather than an aspiration.

That is the point. Not gamification as entertainment. Gamification as a disciplined way to make invisible agreement systems shareable, testable, and collectively governable.

Note: This text reflects conceptual research thinking. It does not describe or assess any specific organization. Examples and situations referenced are synthetic or composite and are used solely for analytical purposes.