Risk work keeps pointing me back to agreements

I’ve been having a lot of conversations recently with people in insurance, banking, and the SME sector who handle risk, and a familiar tension keeps resurfacing. Risk work needs evidence that travels: it must be communicable, defensible, and internally consistent across reviewers and over time. At the same time, much of what makes an SME resilient under pressure is not neatly contained in the artifacts that usually travel well, plans, policies, documents, and governance charts. The most decisive material often lies in patterns of coordination: who can decide what, how exceptions are handled, how conflicts are metabolized, and how learning becomes cumulative rather than episodic. I keep noticing that the technical challenge is not only “assessing risk,” but also assessing what kind of evidence counts as risk evidence in the first place.

Risk is not my research object; it is one of the interfaces where agreement systems reveal their consequences.

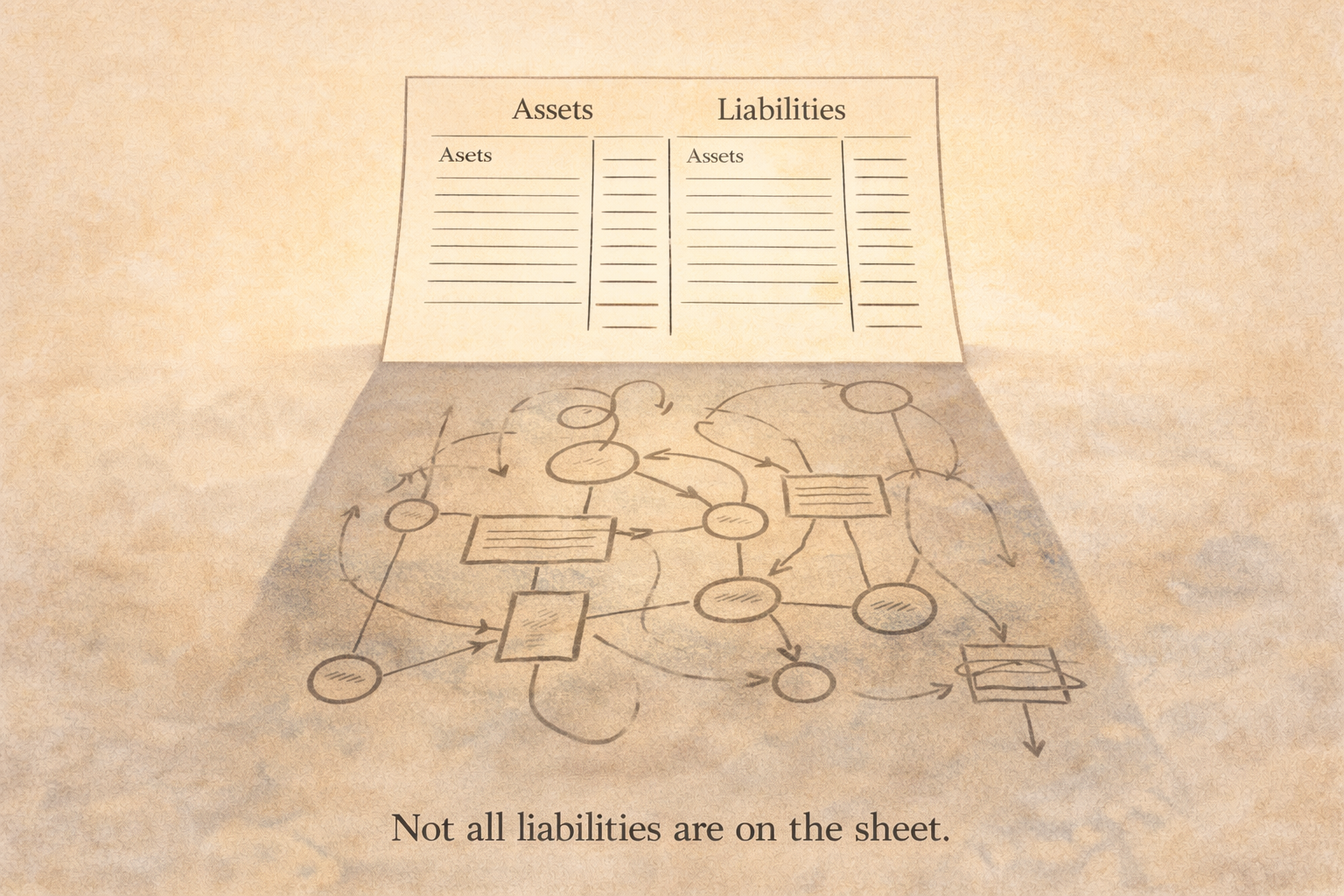

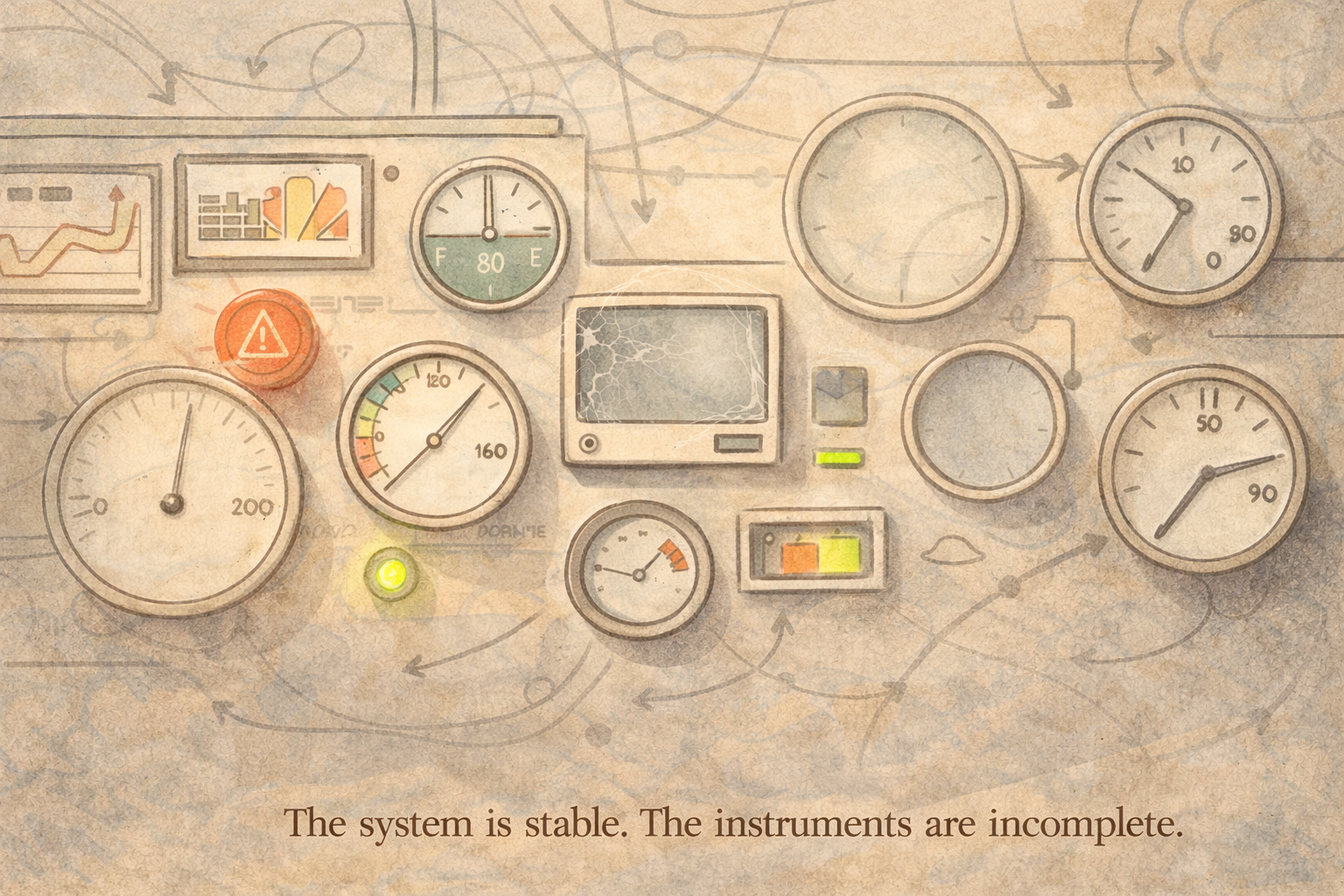

That is a paradigmatic problem before it is a methodological one. When paradigmatic assumptions shift, the ontology of “what is real” and the epistemology of “what is knowable” change with it (Cohen et al., 2018; Neuman, 2014; Hinske, 2025a). In complex social systems, the insistence on clean measurement can quietly select for what is easiest to represent rather than what is structurally decisive. Complexity thinkers have been warning for decades that system behavior is frequently counterintuitive, emergent, and driven by feedback processes that don’t reveal themselves through linear, single-variable explanations (Forrester, 1971; Morin, 2008; Meadows, 2008). When risk is approached as if the system were stable and decomposable, it becomes harder to see how coordination breakdowns incubate long before financial signals become acute.

This is not an argument against quantitative rigor. It is an argument that, in SME ecosystems, what appears to be a “soft” issue can be a structural driver. Systems language helps me name this without moralizing it: patterns persist because they are supported by structure (Meadows, 2008; Senge, 2006). The practical implication for my PhD is that I can’t treat agreements as “culture,” “trust,” or “leadership.” I treat them as coordination infrastructure: the mostly invisible rules that allocate decision rights, define legitimate voice, shape responses to exceptions, and determine whether learning is retained in the system or lost between episodes (Ritchie-Dunham, 2014; Ritchie-Dunham et al., 2024). In that framing, resilience is not a trait. It is an emergent property of an agreement system.

I’ve already explored one implication of this elsewhere: if agreement quality really shapes coordination, translating it into financial risk language requires conservative proxies and explicit assumptions, otherwise, the translation becomes theater rather than evidence.

That shift forces a method choice. Because agreements are often tacit and enacted, the method must work with lived complexity without flattening it into a thin set of variables. This is why I keep returning to case study logic as my core: it is designed for depth, contextuality, and multi-perspectival understanding, and it values significance rather than frequency when the goal is to understand how dynamics actually work (Cohen et al., 2018; Leppäaho, 2024a; Neuman, 2014). But I also don’t want a method that only produces descriptions. I need a way to trace how agreements generate outcomes across interfaces, how they redistribute coordination pressure and how they shape what becomes discussable or taboo within a system.

This is the space where I’ve been shaping what I call a case-informed, action-engaged systems inquiry (CAESI), a hybrid inquiry grammar that uses case depth as the anchor, systems thinking as the explanatory spine, and participatory sensitivity as the way to surface what is otherwise invisible (Leppäaho, 2024a, 2024b; Neuman, 2014; Meadows, 2008). The phrase “action-engaged” is easy to misunderstand. It does not mean turning research into an intervention program. It means acknowledging a methodological point: when the phenomenon is partly tacit, some form of dialogic surfacing is often required to make the structure available for inquiry at all (Cohen et al., 2018; Leppäaho, 2024b). In other words: the inquiry needs a way to bring agreement assumptions into view without relying on retrospective storytelling alone.

I’ve written about this “surfacing discipline” as a ladder: treat felt experience as an entry signal, validate through observation, and move toward agreement footprints as the unit of analysis, so the method stays anchored in coordination reality rather than in narratives about it.

This is where I see my contribution as a bridge, not as a new theory of banking or insurance. I’m trying to make agreement patterns legible as risk-relevant signals, remaining academically disciplined and practically meaningful. The target is not a new scoring system. The target is an evidential move: tracing a chain of evidence that links observed coordination patterns to plausible risk-relevant consequences, while being transparent about assumptions and limits (Cohen et al., 2018; Neuman, 2014). That’s why tools like agreement field mapping and system modeling matter to me, not as “visual facilitation,” but as representational scaffolds that can hold complexity without dissolving it into anecdotes (Scott, 2018; Meadows, 2008). In participatory system dynamics, there is a long tradition of using shared models to support enduring agreement about what is going on, precisely because complex systems invite competing interpretations (Scott, 2018; Forrester, 1971). I’m borrowing that rigor: if a coordination claim matters, it should be representable, interrogable, and traceable.

I also paused on this more directly in a hypothesis note: when “risk prevention capability” sits within ecosystem coordination and agreement health, the central problem becomes legibility, what can count as a credible signal without being seduced by story or by paper-shaped evidence.

One reason this matters in risk conversations is that “risk” is often framed as a property of an entity, an SME, a sector, or a portfolio. My work keeps nudging me toward framing risk as a property of an interaction system: a pattern of agreements across an SME and its stakeholder ecosystem. When I take that seriously, I stop looking for a single root cause and start looking for feedback loops and interconnected footprints: how decisions generate side effects, how side effects create new constraints, and how those constraints shape the next round of decisions (Morin, 2008; Meadows, 2008). In that view, the crucial question is not only “what is the risk exposure,” but also” what is the system’s capacity to notice, negotiate, and adapt before small frictions become expensive events?”

This also explains why I keep returning to learning loops, not as an inspirational idea, but as an epistemic discipline. If my method is meant to operate in complexity, it must include a way to test and refine its own assumptions. Triple-loop learning is one language for that: not only correcting actions (single-loop) and questioning assumptions (double-loop), but also examining the deeper logic that governs what the system treats as learning in the first place (Argyris & Schön, 1978; Torbert et al., 2004; Hinske, 2009). For my PhD, that means staying explicit about where my framing might be overreaching, where my representations might be seductively clean, and where I might be confusing coherence with validity.

Over the years, across those conversations, what has become clearer to me is this: the most challenging part is not saying that agreements matter. Many people intuitively know they do. The tricky part is doing the scholarly and methodological work to make agreement patterns visible enough to be discussed as evidence, without collapsing into either pure measurement fantasy or pure narrative persuasion. That is the intersection I’m working in. It is slow, but it feels structurally necessary: a way to strengthen how we think about risk in SME ecosystems by expanding what can be treated as legible, interrogable coordination evidence, while staying honest about uncertainty, limits, and the fact that complex systems remain partially opaque by nature (Morin, 2008; Maturana & Varela, 1987)

References

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Addison-Wesley.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge.

Forrester, J. W. (1971). Counterintuitive behavior of social systems. Theory and Decision, 2(2), 109–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00148991

Hinske, C. (2009). Triple-loop learning in the context of global environmental change (Unpublished master’s thesis). University for Sustainable Development Eberswalde.

Hinske, C. (10 May 2025). Paradigms in practice: Reflexive comparison of scientific worldviews and bias awareness in research (Unpublished course essay). LUT University, Doctoral Programme in Business & Management.

Leppäaho, T. (2024a). Qualitative case study research. Fundamentals of Scientific Thinking and Research Methodology, LUT University Business School.

Leppäaho, T. (2024b). Other qualitative methods. Fundamentals of Scientific Thinking and Research Methodology, LUT University Business School.

Maturana, H., & Varela, F. (1987). The tree of knowledge. Shambhala Publications.

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer (D. Wright, Ed.). Sustainability Institute.

Morin, E. (2008). On complexity. Hampton Press.

Neuman, W. L. (2014). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (7th ed.). Pearson.

Ritchie-Dunham, J. L. (2014). Ecosynomics: The science of abundance. Vibrancy Publishing.

Ritchie-Dunham, J. L., Chaney Jones, S., Flett, J., Granville-Chapman, K., Pettey, A., Vossler, H., & Lee, M. T. (2024). Love in action: Agreements in a large microfinance bank that scale ecosystem-wide flourishing, organizational impact, and total value generated. Humanistic Management Journal, 9(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41463-024-00182-y

Scott, R. (2018). Group model building: Using systems dynamics to achieve enduring agreement. Springer.

Senge, P. (2006). The fifth discipline. Currency Doubleday.

Torbert, B., Fisher, D., & Rooke, D. (2004). Action inquiry: The secret of timely and transforming leadership. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Cross-referenced PhD Notes

Hinske, C. (31 October 2025). From felt experience to agreement footprints: A CAESI ladder for diagnosing agreement systems. https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/su59c6xvp1xsad1x8vsvsc4vhp9sgf

Hinske, C. (13 November 2025). Survey ≠ diagnosis: Using a valid signal without overclaiming it. https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/survey-diagnosis-using-a-valid-signal-without-overclaiming-it

Hinske, C. (11 December 2025). From agreement quality to financial risk: Conservative translation without fake precision. https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/from-agreement-quality-to-financial-risk-conservative-translation-without-fake-precision

Hinske, C. (29 December 2025). A working hypothesis to test with a bank: When “low-risk” SMEs feel unseen, and how I plan to stress-test the claim. https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/8183oxdr902a2eekzurblcq8ujjwly