The Kwahu Advantage (Ghana)

This post revisits earlier work by Anuwa-Amarh & Hinske (n.d.) and Anuwa-Amarh et al. (2020). I’m staying close to the original argument, but re-reading it through my current PhD focus: ecosystems don’t “work” because they have resources; they work because they have agreement systems that sustain coordination, learning, and inclusion over time.

Why we wrote it then

Entrepreneurship matters for SDG 4 (skills and lifelong learning) and SDG 8 (decent work and inclusive growth). The core claim was that sustained entrepreneurship requires more than focusing on individuals or single firms; it needs an entrepreneurial ecosystem, “a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated” to enable productive entrepreneurship in a territory (Stam & Spigel, 2016; Anuwa-Amarh & Hinske, n.d.).

We used Silicon Valley and China’s platform giants as familiar examples of compounding effects across generations (Berlin, 2010; Jia et al., 2018). The point was not “copy these places,” but that ecosystems build over time through repeated cycles of learning, replication, and capability transfer (Anuwa-Amarh & Hinske, n.d.; Fuerlinger et al., 2015).

What the Kwawu case contributed

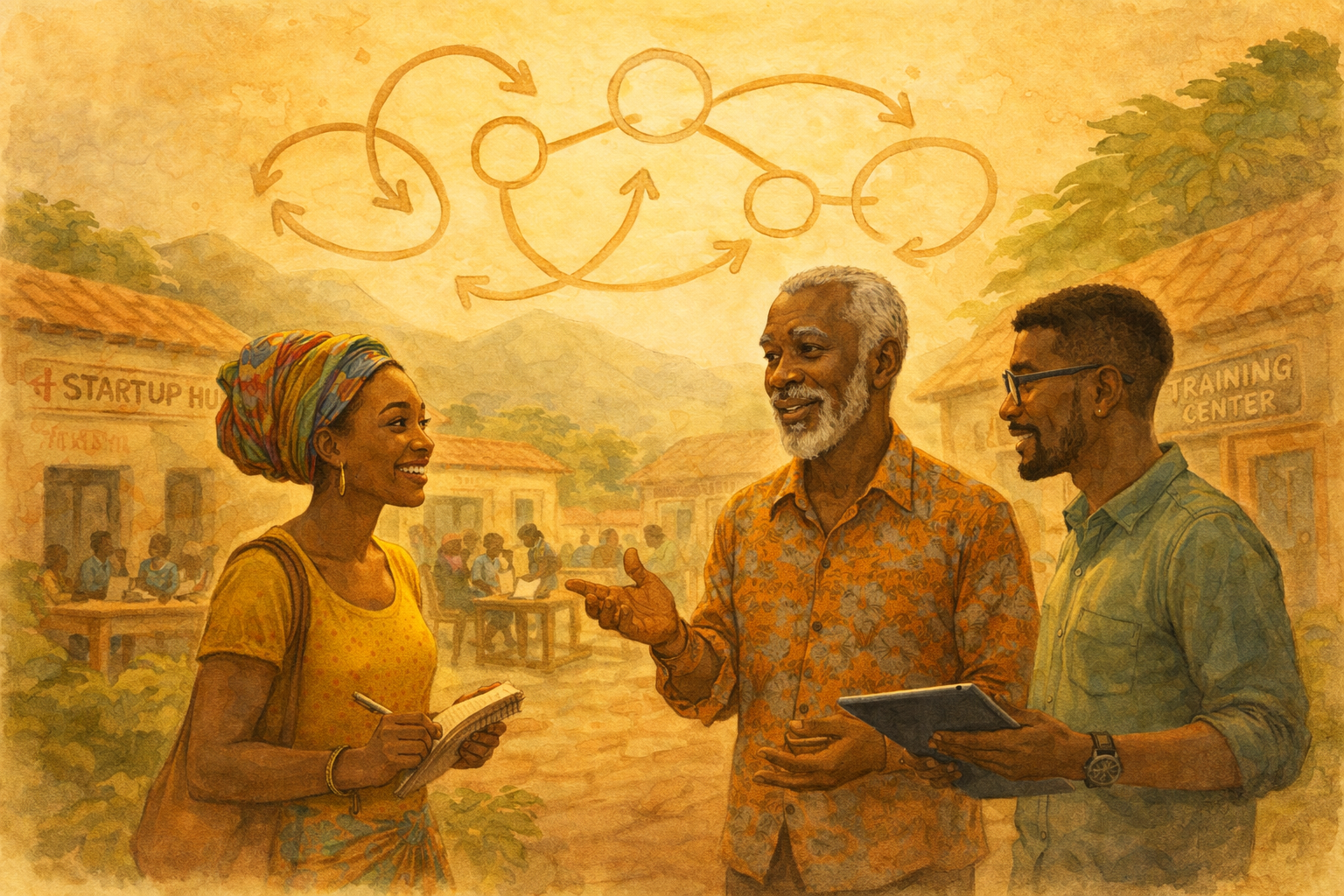

In the Kwawu communities (Ghana), we described a resilient entrepreneurial ecosystem as eight interrelated elements (Anuwa-Amarh & Hinske, n.d.; Anuwa-Amarh et al., 2020):

Enabling an entrepreneurial culture (mentors, trusted capital networks, opportunity “sniffing,” cooperation)

Learning-by-observing (early exposure to entrepreneurial role models)

Learning-by-doing (practice, coaching, excellence through action)

Learning-by-adopting (selecting and embracing proven ethos, technologies, and ways of working)

Learning-by-adapting (adjusting to changing conditions, economic, social, political, technological)

Learning-by-replication (reusing strategies in new markets/locations)

Learning-by-spiriting (“grey hair services”: wisdom stewardship, vision-carrying, community continuity)

Social inclusion as the holding atmosphere that keeps the system open, connective, and mutually sustaining

My PhD re-read: these eight elements describe an agreement system

If I translate the same eight elements through today’s lens, I see something more specific than “culture”:

Kwawu’s resilience stems from agreements that remain workable and renegotiable as the ecosystem scales.

Culture becomes: shared expectations about trust, reciprocity, mentoring obligations, and how access to capital is earned (Anuwa-Amarh & Hinske, n.d.).

Observing + doing become: apprenticeship in how coordination works here, how to enter networks, recover from setbacks, and earn legitimacy (Anuwa-Amarh et al., 2020).

Adopting + adapting become: importing practices and refitting them to local relationships and identity so they actually stick (Anuwa-Amarh & Hinske, n.d.).

Replication becomes: transferring not only “business models” but also portable templates of roles, expectations, and relationship patterns (Anuwa-Amarh & Hinske, n.d.).

Spiriting becomes: stewardship of the ecosystem’s identity, people who keep coherence across generations and help the system learn without fragmenting (Anuwa-Amarh et al., 2020).

Social inclusion becomes: boundary agreements, how newcomers join, how difference is integrated, and how mutual benefit remains real rather than symbolic (Anuwa-Amarh & Hinske, n.d.).

Practical takeaway for SDG 4 and SDG 8

If ecosystems are partly agreement systems, then policy and practice shift:

For SDG 4, it’s not enough to deliver training. You also need social learning loops: mentoring pathways, safe ways to fail and return, and spaces where new practices are tested and legitimized (Anuwa-Amarh et al., 2020).

For SDG 8, it’s not enough to incentivize entrepreneurship. You need coordination infrastructure: trust-building mechanisms, dispute-handling norms, and inclusion rules that keep opportunity distributed and collaboration possible (Anuwa-Amarh & Hinske, n.d.).

What I would look for today (the “footprints”)

When I study entrepreneurial ecosystems now, I don’t start with “how many start-ups.” I start with observable agreement footprints:

Where do people renegotiate how they work together (without fear)?

How does the ecosystem restore coordination after shocks?

What makes learning cumulative rather than repeatedly reinvented?

Who protects inclusion in ways that create real access, not just goodwill?

That’s the heart of my current PhD direction: making the invisible coordination layer visible enough to learn from, and to design for, without romanticizing or blaming any one actor.

References

Anuwa-Amarh, E., Hinske, C., Bamfo-Debrah, N. K., Sefa, D., Amarh, S., & Nassam, S. (2020). The Kwawu resilient entrepreneurial ecosystems: A complex adaptive systems approach to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. In Sustainable Development and Resource Productivity (pp. 317–331).

Anuwa-Amarh, E., & Hinske, C. (n.d.). Thought leaders' piece on the Kwawu entrepreneurial ecosystem [Webpage]. Taylor & Francis. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/sdgo/about/leading-thoughts?context=sdgo

Berlin, L. (2010). Robert Noyce, Silicon Valley, and the teamwork behind the high-technology revolution. OAH Magazine of History, 24(1), 33–36.

Fuerlinger, G., Fandl, U., & Funke, T. (2015). The role of the state in the entrepreneurship ecosystem: Insights from Germany. Triple Helix, 2(1), 1–26.

Jia, K., Kenney, M., Mattila, J., & Seppala, T. (2018). The application of artificial intelligence at Chinese digital platform giants: Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent (ETLA Reports No. 81).

Stam, F. C., & Spigel, B. (2016). Entrepreneurial ecosystems (USE Discussion Paper Series, 16(13)).