When Research Becomes Practice: Designing Impact Without Value-Smuggling

Course Essay at Lappeenranta-Lahti University of Technology LUT - A350AJ700 Sustainability and Impact in Business Research

Assignment: Reflection paper 4/5 — How will my research impact business practice?

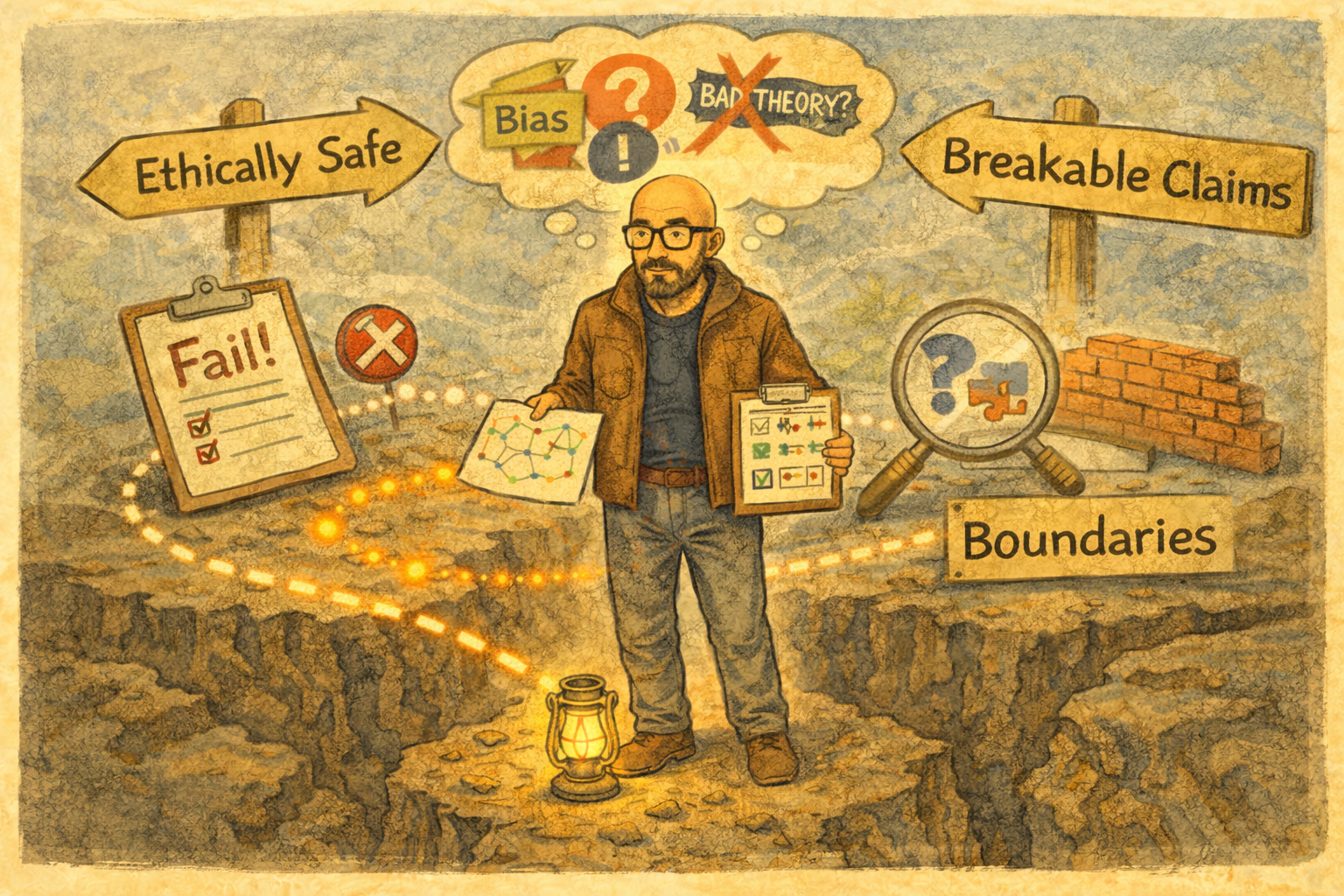

Image 1: Impact without ideology: making coordination inspectable, naming values up front, and keeping claims breakable through boundaries, rivals, and disconfirming cases.

My research will affect businesses by changing what managers and stakeholders consider evidence of coordination, risk prevention, and value creation in small- and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) and their ecosystems. I do not mainly offer a new moral story or recommendations. I provide a method for noticing, identifying, and checking what is usually invisible: the agreements people make as they work together, including the actions and shared understandings that shape decisions, handoffs, exceptions, conflict resolution, and learning. This impact is strong, but it also brings a duty: once a way of observing spreads, it can start to create the conditions it describes. (Ghoshal, 2005; Hinske, 2025a)

Reading Ghoshal helped me see more clearly that a core feature of my CAESI approach is already a built-in safeguard against value-smuggling behind "fake objectivity." I start every stakeholder dialogue by stating I am not objective but consciously subjective. I enter as a situated researcher with biases, norms, and values that shape what I notice, what I ask, and what I interpret. I explicitly invite my conversation partner to push back and treat the next 35 to 45 minutes as a joint exploratory "dance." In this, we co-test my framing rather than consume it. This makes the normative and performative effects of concepts discussable in real time, instead of leaving them implicit and pretending neutrality. (Ghoshal, 2005; Hinske, 2026)

Same warning, different words

This assignment made me see that Ghoshal is pointing at a risk that others describe with different labels: once an idea “travels” into practice, it can start shaping the behavior it claims to describe (Ghoshal, 2005). That clicked immediately with my earlier studies in systems thinking and system dynamics, as well as my interest in relational framings of human interaction in organizations (Senge, 1990, 2006; Hüther, 2017).

Concretely, if “agreement debt” or “agreement footprints” ever turns into a target, score, or compliance ritual, it can trigger perverse incentives (the Cobra Effect): people optimize what is measured, not what matters (Siebert, 2001; Lucas, 2018). In systems language, this is Fixes That Fail: a quick, symptomatic fix reduces pain in the short term but creates delayed side effects that recreate the problem (Kim, 2000; Senge, 1990, 2006). It also aligns with Shifting the Burden: the organization keeps applying quick relief and underinvests in the slower capability-building work of strengthening real negotiation capacity and learning loops (Kim, 2000; Senge, 1990, 2006).

Rather than treating this only as a safeguard, I read it as confirmation that my interview design is pointed in the right direction. In the subject-subject sense described by Hunziker and Hüther, the decisive shift is not a communication trick but an orientation: meeting the other as a subject with their own aims and meanings, and allowing something new to emerge in the encounter instead of reducing the person to an object of diagnosis or extraction (Hunziker & Hüther, 2016; Maas, 2017). That is exactly why I start dialogues by naming my situatedness and inviting pushback: the conversation becomes a joint inquiry where interpretations are co-tested in real time, not a one-way capture of “data.” Epistemologically, this aligns with Cohen et al.'s description of a central feature of social inquiry: the world under study is already interpreted by participants, and the researcher’s account is necessarily produced in relation to those interpretations rather than outside them (Cohen et al., 2018). In practice, this means my concepts are introduced as revisable hypotheses anchored in concrete episodes, with explicit space for disconfirming cases and rival framings, so that “agreement debt” and “agreement footprints” remain shared lenses for sensemaking instead of becoming managerial labels imposed on others (Cohen et al., 2018; Hunziker & Hüther, 2016; Hinske, 2025e).

Ghoshal’s warning matters because my work sits at the point where ideas become managerial common sense. When I publish frames (conceptual ways to interpret phenomena) like “agreement debt” (unaddressed obligations from implicit or incomplete agreements) or “agreement footprints” (traces of agreements shaping outcomes), I am not just describing patterns; I am creating them. I propose a vocabulary that guides attention, justifies interventions, and shapes how people act under pressure. If that vocabulary becomes simplistic, it could legitimize harmful management, even if I intend otherwise. That is my first critical risk: my research could become a clean-sounding theory that narrows moral imagination and makes complex coordination seem like technical problems with “agreement quality” (Ghoshal, 2005; Kirchherr, 2023).

This is why I see my public writing as part of my research, not just an extra activity. On 360dialogues.com, I share "PhD Notes" to publicly document my learning process and avoid giving direct advice. I avoid recommendations because they can turn learning into quick fixes and stop real change. (Hinske, 2025b) If I tell companies what to do, I might create surface-level agreement and miss seeing how real agreement happens under pressure. (Hinske, 2025b) My goal is to help people see more clearly, so they can run better experiments in their own work. (Hinske, 2026)

However, Healy’s provocation forces me to be honest about a second risk: my blog format rewards crisp mechanisms and clean takeaways. Even when I explicitly reject fake precision, I still benefit from rhetorical clarity. (Healy, 2017; Hinske, 2025a) The danger is not that I lack nuance. The danger is that my abstractions become too elastic to be wrong. If every counterexample can be absorbed as “the system is complex,” then the frame is not doing scientific work. (Healy, 2017) Applying Healy to my own PhD thinking, I treat this as a design constraint: I must keep my core concepts and claims open to revision by stating boundary conditions, naming rival explanations, and publishing disconfirming cases rather than allowing “agreement infrastructure” to become an all-explaining vocabulary. (Healy, 2017) So, if my research is to impact practice responsibly, I must make fewer, sharper claims that can be stress-tested by practitioners and can fail in public. That means publishing not only “what seems to work,” but also disconfirming episodes, boundary conditions, and cases where the agreement-footprint lens misleads. (Healy, 2017; Ghoshal, 2005)

Kirchherr’s critique of “bullshit” in the sustainability and transitions literature adds a third, very concrete accountability pressure. I operate in a discourse space that is saturated with attractive language: circularity, regeneration, flourishing, ecosystems, transitions. (Kirchherr, 2023; Lehmann et al., 2023) Even if my work is empirically grounded, it can still get pulled into the same incentive structure: impressive words that travel faster than operational definitions. (Kirchherr, 2023) My countermeasure has been to anchor my concepts in observable residues and conservative translations, for instance, translating coordination patterns into decision latency, coordination overhead, and talent drain without pretending to quantify causal effects prematurely. (Hinske, 2025a) Yet Kirchherr’s challenge remains: unless I keep specifying measurement rules and non-examples, my own vocabulary can become the kind of high-status language I claim to resist. (Kirchherr, 2023)

My role as co-editor multiplies both reach and responsibility. In Factor X 5 - The Impossibilities of the Circular Economy and Factor X 6 - Resource Systems for Human Flourishing, we explicitly separate aspiration from reality. We invite readers to face constraints, rather than celebrate narratives. (Lehmann et al., 2023) This editorial stance can influence business practice by legitimising harder conversations in boardrooms and policy spaces. This is especially important when circular economy discourse is used as a comfort blanket. (Hinske et al., forthcoming; Lehmann et al., 2023; Kirchherr, 2023) But editorial platforms also create a risk. They can become megaphones for elegant critique that produces status rather than changed practices. To avoid that, my research impact must remain tied to instruments that change how decisions are made, not only to arguments that win debates. (Ghoshal, 2005; Healy, 2017)

This is where engaged scholarship, in Hoffman’s sense, is not just a value statement for me. It is a governance choice about where I place my work and how I expose it to civic and practitioner spaces. (Hoffman, 2021) My Factor X series work and the 360dialogues platform are part of that engagement infrastructure. They are designed to circulate ideas, recruit dialogue partners, and make scholarly work legible outside narrow academic channels. (Hinske, 2025c; Hinske, 2025d) I also have evidence of reach, including the Factor X comic traffic numbers and the multilingual distribution logic described on the series page. (Hinske, n.d.-a) Still, I cannot treat reach as a proxy for impact quality. A widely shared frame can still be wrong, harmful, or mainly performative. (Ghoshal, 2005; Kirchherr, 2023)

So the simplest way to explain my research’s impact on business is this: it shifts what counts as valid knowledge between SMEs and their stakeholders. Instead of using reports that are easy to make but often untrustworthy (policies, charts, glossy strategies), it asks stakeholders to find real evidence in specific situations showing how agreements actually work, then turn this evidence into testable assumptions about risk and coordination. (Hinske, 2026; Hinske, 2025a) If this works, it could help avoid dismissing strong firms just because their resilience is hard to see and stop weak systems from hiding behind paperwork. (Hinske, 2025a) But I also have clear responsibilities: I must stop my research from becoming empty management theory, keep my claims open to challenge, and avoid using empty buzzwords by sticking to practical methods and publishing failures. (Ghoshal, 2005; Healy, 2017; Kirchherr, 2023)

Finally, I accept that my impact profile may not optimise for the most citations in the “research universe,” and I do not need to apologise for that. Engaged scholarship still requires rigor, but it measures success partly by whether ideas improve collective sensemaking where decisions happen. (Hoffman, 2021) My responsibility is to ensure that the impact I already have, including through editorial work and public writing, is not only visible but also epistemically clean and ethically safe. (Ghoshal, 2005; Kirchherr, 2023)

References

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Research-Methods-in-Education/Cohen-Manion-Morrison/p/book/9781138209886

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2005.16132558

Healy, K. (2017). Fuck nuance. Sociological Theory, 35(2), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275117709046

Hinske, C. (2025a). From agreement quality to financial risk: Conservative translation without fake precision. 360Dialogues. Retrieved 6 February 2026, from https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/from-agreement-quality-to-financial-risk-conservative-translation-without-fake-precision

Hinske, C. (2025b). Giving back without consulting: Why I refuse recommendations. 360Dialogues. Retrieved 6 February 2026, from https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/giving-back-without-consulting-why-i-refuse-recommendations

Hinske, C. (2025c). Factor X Series. 360Dialogues. Retrieved 6 February 2026, from https://360dialogues.com/factor-x-series

Hinske, C. (2025d). PhD Notes. 360Dialogues. Retrieved 6 February 2026, from https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes

Hinske, C. (2025e). Paradigms in Practice: Reflexive comparison of scientific worldviews and bias awareness in research [Unpublished course essay]. LUT University, Doctoral Programme in Business & Management. —> Access Essay

Hinske, C. (2026). A 35-minute interview that produces evidence. 360Dialogues. Retrieved 6 February 2026, from https://360dialogues.com/phd-notes/a-35-minute-interview-that-produces-evidence

Hinske, C., Ritchie-Dunham, J., Lehmann, H. (Eds.). (forthcoming). Resource Systems For Human Flourishing: Aligning Agreements with the Conditions for Life to Thrive. Routledge.

Hoffman, A. J. (2021). The engaged scholar: Expanding the impact of academic research in today’s world. Stanford University Press.

Hunziker, D., & Hüther, G. (2016). Wie lässt sich erklären, was eine Subjekt-Subjekt-Beziehung ist? Versuch einer Begriffsklärung im Dialog [PDF]. Akademie für Potentialentfaltung. https://www.akademiefuerpotentialentfaltung.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Was-ist-eine-Subjekt-Subjekt-Beziehung.pdf

Kim, D. H. (2000). Systems archetypes I: Diagnosing systemic issues and designing high-leverage interventions (Toolbox Reprint Series). Pegasus Communications. https://thesystemsthinker.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Systems-Archetypes-I-TRSA01_pk.pdf

Kirchherr, J. (2023). Bullshit in the sustainability and transitions literature: A provocation. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 3, 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-022-00175-9

Lehmann, H., Hinske, C., de Margerie, V., & Nikolova, A. S. (Eds.). (2023). The impossibilities of the circular economy: Separating aspirations from reality. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003244196

Lucas, D. S., & Fuller, C. S. (2018). Bounties, grants, and market-making entrepreneurship. The Independent Review, 22(4), 507–528. https://www.independent.org/wp-content/uploads/tir/2018/04/tir_22_4_02_lucas.pdf

Maas, A. (2017). Die Lösung liegt in der Co-Kreativität (Interview mit Prof. Dr. Gerald Hüther). maaS: Impulse für ein erfülltes Leben, Heft 4, 56–61. Akademie für Potentialentfaltung. https://www.gerald-huether.de/free/maas_huether.pdf

Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday/Currency.

Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization (Rev. and updated ed.). Doubleday.

Siebert, H. (2001). Der Kobra-Effekt: Wie man Irrwege der Wirtschaftspolitik vermeidet. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.