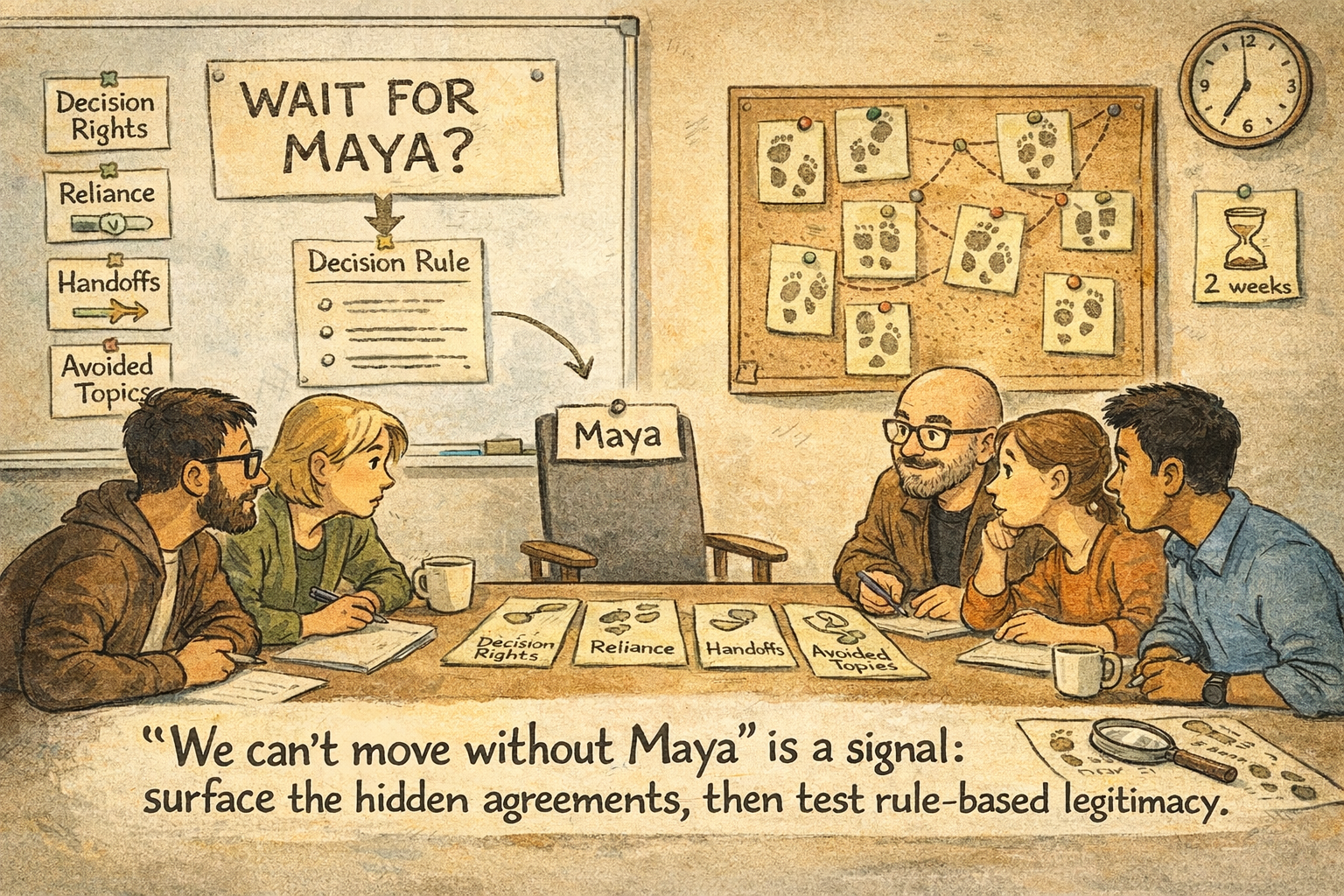

When a System Says “We Can’t Move Without Maya”

A field episode showing how I use the Agreement Card Deck as a research method (a follow-up to “From Diagnosis to Stakeholder Play”).

In my earlier post, “From Diagnosis to Stakeholder Play: Using a Card Deck to Make Agreement Systems Shareable,” I described a recurring request: “Can we gamify this?”—and why that’s risky when it turns into scoring. Scoring invites the wrong optimization: protect face, optimize the number, and hide the truth. Instead, I use the deck as a structured way to make agreement systems discussable as a shared object of attention—playful enough to lower defensiveness, strict enough to demand evidence and testing.

That post also named the non-negotiable design rule that holds the whole method together: every card must end with four fields—a concrete claim about coordination reality, footprints (evidence), the implied cost/risk logic under uncertainty, and a micro-experiment. If a group can “finish” a card without leaving footprints or taking a test, the card is not doing its job.

This follow-up is a “show it in practice” piece. It uses a single field episode in a mid-sized, multi-stakeholder organization to show how I use the deck as a research instrument. The goal here is not to be clever. The goal is to be traceable: one episode, role-anchored footprints, explicit assumptions, and small tests that can generate new evidence fast. This is the bridge I care about: moving from what the analyst sees to what the stakeholder field can test.

The episode I anchored: progress that waits for one person

The organization had real external dependencies—partners with their own timelines, reputational risk if commitments slipped, and internal teams whose work had to land cleanly across boundaries. Meetings were not chaotic. People were capable. Yet the project kept stalling in a way that felt oddly normalized.

Across several interactions, the same sentence appeared in different forms for different processes:

“Let’s wait until Maya weighs in.”

" This needs Maya.”

" Wecan'tt really move without Maya.”

The paradox is the data point: Maya is not the designated owner, yet the system behaves as if she is the condition for progress. That mismatch—high dependence, low mandate—is what the cards helped make visible.

Nobody used dramatic language. It wasn’t framed as a bottleneck. It was presented as realism—as if the system were describing physics. But in research terms, that sentence is not a personality story. It is a coordination claim in disguise. Whenever a group says “we can’t move without X,” it often signals an agreement system that has become person-bound: legitimacy routes through an individual, handoffs rely on informal bridging, and governance topics remain implicit until they reappear as dependencies.

To keep the inquiry grounded, I anchored one concrete episode rather than discussing “how we are.” The episode had a clear shape:

A partner-facing decision point was on the agenda. The group had discussed it before. There was rough alignment on intent. Still, nobody made a decision. The conversation circled: more context, more hedging, more “just to be safe.” Then someone said, almost lovingly, “Let’s not decide this without Maya—she knows what the partners will accept.” The outcome was predictable: the decision was deferred, a follow-up meeting was scheduled, and parallel work paused because downstream teams didn’t know which assumptions to build on.

That gave me exactly what the method needs: a single coordination episode with a trigger, a decision/handoff point, and an observable outcome.

How I framed it as research (without turning it into consulting)

Before introducing any cards, I used a short opening script. I’m explicit because it keeps the room usable and the method honest:

This aligns with the stance in the earlier post: the deck exists to prevent the collapse of working explanation into advice and to force the move from “we think” to “we can point to.”

Because readers don’t have my private templates, I’ll describe the two one-page tools I use in plain language. One is a live facilitation checklist—a way to stay disciplined under social pressure. It forces me to (1) choose one episode, (2) timebox, (3) pick only a few cards from the core set, and (4) finish each card with footprints and a test. The second is a field log—a one-page record that captures the episode in a form comparable across cases: roles present, episode title, cards used, footprints with confidence tags, assumptions, and the micro-experiments with a named host role, time window, signals, and a stop/revert rule.

I then ran the canonical flow exactly as described in the earlier post: establish the stakeholder field, surface footprints, formulate hypotheses, and design micro-experiments. The only difference was timeboxing: this was a compact research episode, not a mapping exercise.

The cards I chose (and why I stopped at four)

In the earlier post, I listed the ten cards I start with because abundance kills inquiry. Too many prompts turn the session into brainstorming, and brainstorming hides reality under creativity. For this episode, the pattern “we can’t move without Maya” strongly pointed to four cards in that core set:

I also briefly touched on Card #5 — Who gets seen/forgotten — because person-bound legitimacy often hides a stakeholder-field mismatch. What matters is not the list. What matters is that each card produces a disciplined arc: prompt → what was said/observed → footprints → cost/risk logic → assumption → micro-experiment.

-

The prompt is simple: who decides, and how does that decision become legitimate across the field?

When I asked it, the room first offered names and job titles. That’s typical. Then the hesitation began. People could describe formal authority in theory, but they struggled to explain what makes a decision stick when Maya isn’t present. In other words, decision authority existed on paper, but legitimacy in practice was routed through one person’s presence.

The footprints came quickly once the question was on the table. People referenced repeated phrases in chat threads: “Let’s check with Maya.” They recalled decisions that were “made” and then reopened later because “Maya hadn’t weighed in.” They pointed to downstream pauses: teams delaying work because they expected the decision to change once Maya reviewed it.

The cost/risk logic was not dramatic, but it was unmistakable. If legitimacy is person-bound, the system pays a tax in decision latency: cycles slow, work waits, and late changes multiply. Under uncertainty, that latency is not just cost; it’s risk, because timing windows with partners close and credibility erodes.

We framed the assumption in a testable way: If legitimacy routes through Maya’s presence, then decisions made without her will be reopened or bypassed in subtle ways.

The micro-experiment we defined was intentionally boring: choose one decision type that repeats often, and publish a short decision rule for the next two weeks—what counts as a decision, who decides, what inputs are required, and how the decision becomes final. Then observe whether reopens and bypasses decrease.

No speeches about governance. Just a small test that produces new evidence.

-

The next prompt: which agreements do we rely on without naming them?

This is where the polite phrase “we can’t move without Maya” became an explicit coordination reality. Underneath the deferrals sat a tacit reliance agreement that nobody had negotiated but everyone obeyed:

When the decision is externally sensitive, Maya will carry it, because she holds key partner relationships and can predict what will be accepted.

Once that was said out loud, the mood shifted—not into blame, but into clarity. People weren’t accusing Maya of controlling things. They were naming a hidden contract the system had written as a coping mechanism for uncertainty.

The footprints matched the claim. Escalations routed to Maya by default. Partner-facing emails drafted and held until she reviewed them. Internal roles saying “I don’t want to commit without Maya because she’ll have to manage the relationship if it goes wrong.” That last one is an especially important footprint: it shows how risk gets displaced onto the same person who also holds legitimacy.

The cost/risk logic here is sharper than it looks. A hidden reliance agreement concentrates external legitimacy and internal coordination power in one role. That can be efficient in calm conditions. Under load, it becomes fragile. Capacity bottlenecks get normalized, and the organization starts to confuse “this is how we work” with “this is unavoidable.”

We formulated the assumption: If externally sensitive coordination relies on one person, then load and uncertainty will repeatedly route decisions to that person, even when formal authority exists elsewhere.

The micro-experiment was not “redistribute everything.” That’s a transformation program disguised as action. Instead, we chose one interface where the reliance showed up most—partner-facing commitments—and designed a two-week test: a different role hosts the interface, with an explicit escalation rule and a defined “what must be true before we escalate.” The point was to see whether legitimacy could be redesigned as a rule rather than a person.

-

This card asks: where do responsibilities evaporate at interfaces—internally or with partners?

This is the card that explains why “just assign someone else” usually fails. In this episode, multiple people had tried to “take over pieces” from Maya. Yet work still bounced back to her. When we looked at handoffs, the reason became visible: interfaces weren’t defined as agreements with boundary conditions. They were handled as social favors.

Under low pressure, social handoffs feel smooth: you can ask, clarify, and patch as you go. Under pressure, social handoffs collapse into rework because assumptions are missing and “done” isn’t defined. That is exactly when the system pulls work back toward the person who can bridge gaps informally—and the invisible owner trap tightens.

The footprints were practical: deliverables arriving “almost done” but not usable because key context wasn’t transferred; repeated re-explanation of partner constraints; downstream teams doing compensating work because “it wasn’t clear what was agreed.”

The cost/risk logic is the coordination tax again, but now it shows up as rework and quality instability. Under external uncertainty, rework becomes risk because it increases the probability of late delivery, poor partner experience, or internal burnout.

The assumption we wrote: If handoffs are social rather than structural, then under time pressure rework loops will spike, and decisions will be routed back to the informal bridge role.

The micro-experiment was precise: pick one recurring handoff that touches external commitments, add a five-line “done means…” checklist, and name a host role on both sides for two weeks. Then track rework incidents and missing-context moments. If the checklist slows throughput, we shrink scope—not abandon the test.

-

Finally: what do we avoid talking about even though it shapes outcomes?

This is often the turning point, because it names what everyone senses but no one wants to be “the person” to say.

In this episode, the avoided topics were governance topics: mandate, legitimacy, ownership, status differences, and what it actually means to be accountable for an external relationship. The group wasn’t conflict-averse. They were governance-averse. They treated power talk as political and therefore unsafe. As a result, power returned through the side door—as dependency, waiting, and implicit escalation.

The footprints were almost audible: jokes that deflected when mandate came up; phrases like “we don’t need to formalize it” paired with repeated “we need Maya”; and a subtle rule that nobody wanted to own the question “Who can decide this in a way that others will accept?”

The cost/risk logic is straightforward: avoided mandate conversations don’t remove politics; they privatize it. The system then pays for that avoidance through bottlenecks.

We wrote the assumption: If mandate and legitimacy topics remain avoided, dependency will persist even after role redistribution attempts.

The micro-experiment wasn’t to “solve politics.” It was to run a single, timeboxed conversation with a strict rule: no personality talk, only assumptions. We wrote down competing assumptions about mandate and legitimacy, and we agreed on one temporary rule to test next cycle. The purpose was not agreement on truth; it was agreement on what reality test we would run.

-

Below is an example of how I capture the episode as comparable research data. You can replicate this without any templates—just copy the headings.

Participants (roles): Program Lead; Partnership Lead; Operations Lead; Senior Specialist; Finance Liaison

Episode title: “Wait for Maya”

Time window: last 6–8 weeks (recent enough to verify traces)

Cards used: #1 Decision rights & legitimacy; #2 Reliance agreements; #13 Boundaries & handoffs; #9 Avoided topics (+ brief #5 Who gets seen/forgotten)Footprints (with confidence):

“Let’s wait until Maya” appears repeatedly in notes/chat (High)

Decisions are reopened when Maya was absent (Medium)

Downstream work pauses because “final” commitments aren’t trusted (High)

Handoffs arrive without key assumptions; rework follows (Medium)

Partner-facing commitments are escalated to Maya by default (High)

Working assumptions:

A1) Legitimacy for externally sensitive decisions is person-bound (routes through Maya).

A2) Reliance agreements and handoff ambiguity pull coordination back to the same informal bridge role.

A3) Avoided mandate talk sustains dependency, even when tasks are redistributed.

Micro-experiments (two-week cycle unless noted):

E1) Decision rule test (Owner: Program Lead). Publish a short rule for one decision type: who decides, required inputs, what makes it final. Signals: reopen/bypass count; time-to-closure. Stop/revert: if conflict escalates, revert and log why.

E2) Handoff interface test (Owners: Ops Lead + Senior Specialist). Add “done means…” checklist + named host on both sides for one recurring handoff. Signals: rework loops; missing-context moments. Stop/revert: if throughput drops, narrow to one deliverable.

E3) Avoided-topic test (Owner: Partnership Lead; one 30-minute session + two-week observation). Document mandate/legitimacy assumptions; agree one temporary rule for the next cycle. Signals: fewer “needs Maya” deferrals; clearer escalation thresholds. Stop/revert: if it becomes personal, end and return to footprints only.

Read-back question: “Is this a fair description of what we can point to?” (Yes, with minor wording edits.)

This snapshot is the research asset. It’s what lets you return in two weeks and ask: did the footprints change? Did dependency shift from person-bound to rule-bound? Did handoffs become more structural? If not, what did we learn?

The close: how you can run this as micro-research in your own context

If you want to try this yourself, don’t start with “our culture.” Start with a real episode from the past month in which coordination stalled, escalated, or was resolved downstream. Then pick two to four cards from the core set and apply the four-field rule each time: claim, footprints, cost/risk logic, micro-experiment. Keep the output small: a short evidence list, a few testable assumptions, and one to three micro-experiments with a named host and a two-week window.

The pattern behind this episode is clear: when a system says “we can’t move without X,” treat it as a signal about decision legitimacy, reliance agreements, handoffs, and avoided topics—not as a personality story. The deck helps because it makes that signal discussable without blame and is strict enough to produce tests rather than theater.

Note: This is a composite, non-attributable field vignette. It illustrates coordination patterns and the use of research methods, not any identifiable organization or individual.