When a System Reveals Its De Facto Goal: What Misaligned Agreements Teach Us

This reflection draws on systems thinking to explore how everyday coordination failures reveal a system’s de facto goals. It also draws on insights from flourishing and self-determination theory to understand how these patterns shape people’s sense of agency and well-being.

-

Over the past years, my research on agreements has taken me into boardrooms, SMEs, public institutions, and national federations. Most of my writing focuses on the ecosystem level—how agreements shape resilience and flourishing across networks of organizations.

Yet sometimes a small moment within a single organization reveals a pattern far larger. What I describe here is not an isolated incident. It is a crystallized example of a recurring structure I have observed and documented over the past years within several organizations I supported. Only later, with the development of CAESI (my Case-Informed, Action-Engaged Systems Inquiry approach; Hinske, 2025), did I finally gain a language precise enough to describe what I had already been seeing in practice.

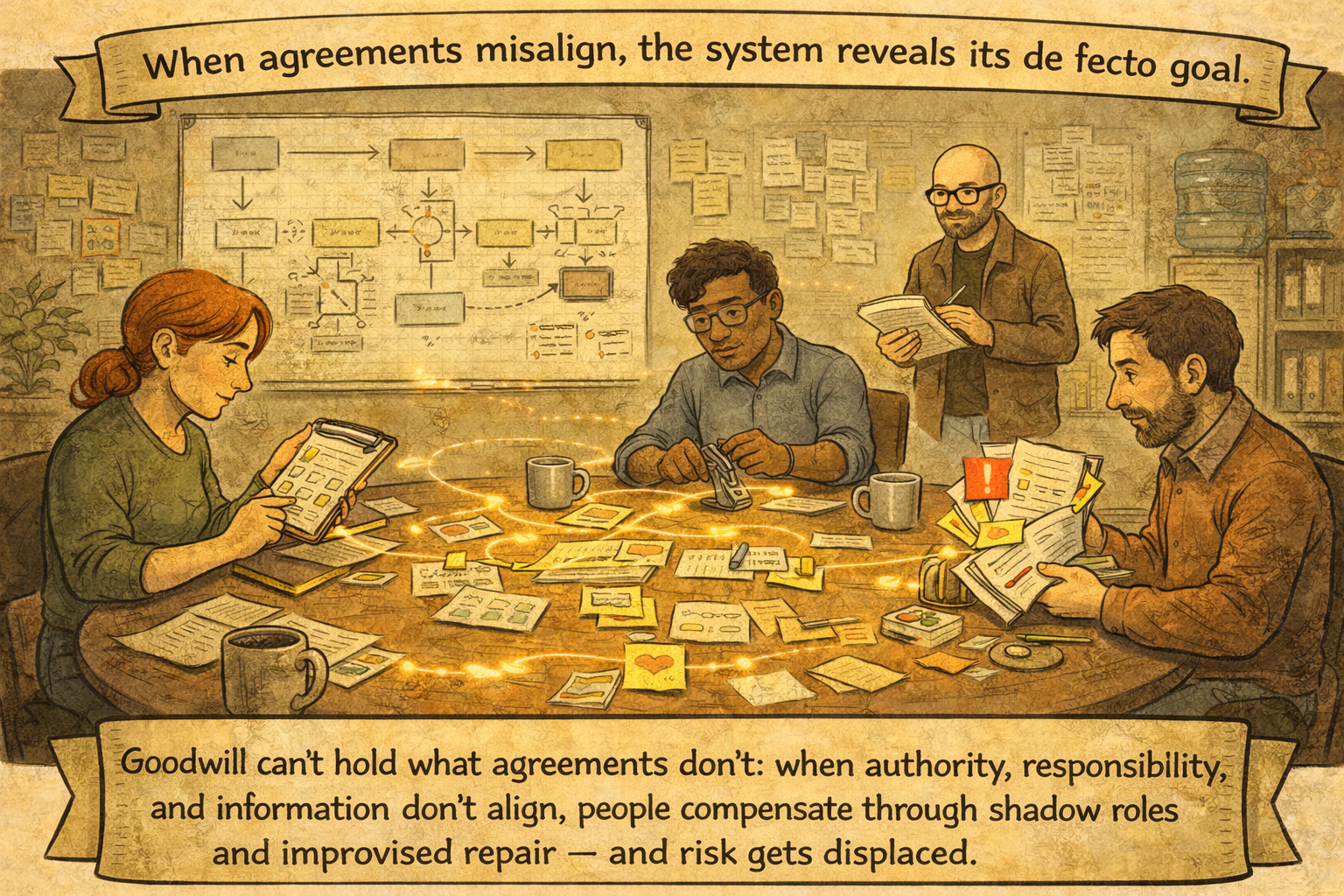

Recently, during a project engagement, one of these moments occurred again: expectations, responsibilities, and decision-making rights were visibly misaligned. On paper, the organization appeared well-structured, with clear roles, defined processes, and a formal hierarchy. In practice, however, the agreements holding the system together were contradictory. People were expected to make decisions without the authority, competencies, or information needed to do so. Leaders were accountable for processes they did not fully understand. And employees quietly compensated for structural gaps—making ad hoc judgments, repairing uncertain workflows, or correcting well-intentioned but risky decisions made upstream.

-

None of this was malicious. Everyone involved was trying their best.

However, the underlying agreements did not align with reality.

In the organization I supported, these misalignments didn’t only appear as inefficiencies. They show up in people’s bodies and daily behaviour: increased vigilance, constant double-checking, filling gaps that do not belong to them, and carrying an invisible load of “making things work.” In many cases, these gaps generate what I call shadow roles: unofficial responsibilities individuals assume simply because the system requires someone to maintain coherence.

I saw these shadow roles emerge consistently whenever formal agreements diverged from lived reality. Their significance becomes visible only when the system stops functioning correctly. Similar dynamics have long been described in the literature as invisible work—the unrecognized coordination and repair labour that sustains formal processes (Star & Strauss, 1999)—and as articulation work, through which people “fit work back together” when formal responsibilities do not align with situational demands (Strauss, 1988).

This is not an individual failing; it is a systemic signal that agreements are not enabling coherent action.

-

From an agreements perspective, the pattern was familiar: the system required individuals to supply coherence that the structure itself did not enable.

Organizational learning scholars have described this misalignment as the gap between espoused theory and theories-in-use (Argyris & Schön, 1978). Systems theorists frame it as the tension between nominal goals—what a system claims to value—and its de facto goals, which can only be inferred from its behaviour (Meadows, 2008).

In my own methodological approach, Case-Informed, Action-Engaged Systems Inquiry (CAESI), I use this distinction as a diagnostic compass. It helps me look past narratives and examine whether lived agreements actually support the regenerative patterns they claim to pursue (Hinske, 2025). Even though CAESI did not exist when I started documenting these dynamics two years ago, it has since enabled me to integrate these recurring patterns into a coherent analytical framework.

In terms of the Agreements Field, what unfolded in this moment was an extractive pattern.

-

Extraction becomes visible when:

Responsibility and authority are disconnected,

processes require competencies not provided,

decision rights are unclear or inconsistent,

individuals must bridge structural gaps by improvising.

These misalignments showed up not only in formal metrics but in embodied tension and quiet compensatory labour.

Throughout my repeated professional engagements with this organization, I saw that people feel extraction long before the system notices it. Their bodies register it. Their attention shifts to vigilance. Their work becomes less about contribution and more about improvised repair.

One of the clearest signals is risk displacement: the system stops holding the risks that belong to it, and individuals begin absorbing legal, procedural, or decision-related risks they were never meant to carry. This is well documented as risk-shifting (Power, 2004) and responsibilization (Hood, 2011).

When this happens, extraction moves from a structural phenomenon into lived experience.

-

The consequences are predictable:

stress, friction, and inefficiency,

decisions that drift outside the organization’s legal or procedural boundaries.

More importantly, extraction drains energy from people rather than strengthening the system as described by Ritchie-Dunham (2024).

Through sustained observation, I learned that when improvisation becomes the primary coordination mechanism, something important is already breaking down. Improvisation stops being a sign of creativity and becomes a diagnostic marker: the structure is no longer holding.

Systems reveal their true agreements at their points of failure—when formal structures collapse into improvisation and the lived architecture of coordination becomes visible.

These moments reveal not what the system claims to value, but what it actually enables (see above: theories-in-use/ de facto goals).

-

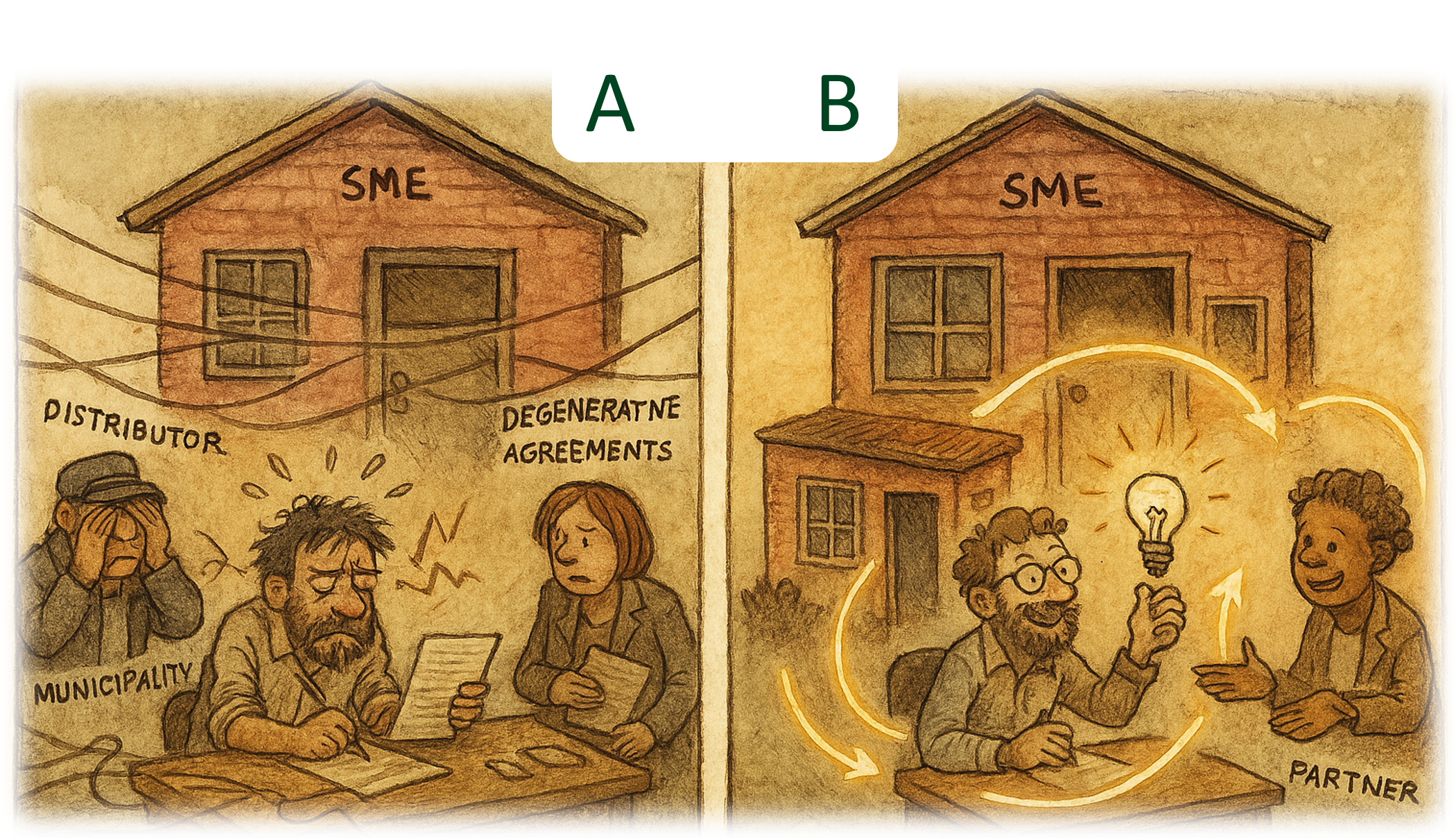

This reflection connects directly to what I explored in earlier blogs. In Exploring Agreements for Ecosystem-Wide Flourishing, I argued that leaders often overestimate the health of their agreements, assuming that conversational goodwill is enough to coordinate complex realities. And in Agreements as a Lever, senior leaders of a national business federation recognized how collapse patterns structurally reproduce across entire ecosystems (see Image 1, Pattern A).

What I encountered in this moment is the same pattern at a smaller scale—a local expression of a systemic structure that I have seen repeat consistently over the past two years.

Pattern A (left): Misaligned or degenerative agreements drain energy, displace risk onto individuals, and trap SMEs in ongoing stress and inefficiency.

Pattern B (right): Regenerative agreements create value, strengthen resilience, and enable an SME to move from A to B—and stay there.

-

Agreements scale unintentionally.

Healthy agreements scale flourishing.

Misaligned agreements scale extraction.

A system does not need bad intentions to generate Pattern A. It only requires unaligned expectations, unclear mandates, or invisible responsibilities embedded in everyday practice.

-

For me, this moment reinforced a central insight from these two years of observation:

Agreements are not abstractions—they are lived.

They shape not only the performance of companies or ecosystems, but

They shape how people experience their work, their agency, and their contribution.

Within CAESI, moments like this are not anecdotal; they are diagnostic. They reveal the difference between a system’s narrative about itself and the lived agreements that actually coordinate behaviour. Minor incidents often illuminate deeper architectures of coordination more reliably than formal documents do.

Across two years of work in this organization, the exact structural mechanism kept appearing: misaligned agreements create extraction, and extraction reveals the system’s real priorities. This simple but powerful insight is my core contribution here. It shows how micro-level incidents can act as diagnostic signals of system health—before stress, conflict, or collapse becomes visible.

I might not use this example as a formal case study for my dissertation, but it was too instructive not to share. It reminded me why aligning agreements is not a soft skill—it is a structural requirement for enabling regenerative capacity, whether in a local team, a business network, or a national ecosystem.

Flourishing is not only a question of what we do. It is a question of what we agree to.

-

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Addison-Wesley.

Hinske, C. (2025, May 17). Comparative exploration of qualitative case study approaches: A reflexive inquiry into case study, narrative, and action-oriented designs [Unpublished course essay]. LUT University, Doctoral Programme in Business & Management.

Hood, C. (2011). The blame game: Spin, bureaucracy, and self-preservation in government. Princeton University Press.

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer (D. Wright, Ed.). Chelsea Green Publishing.

Power, M. (2004). The risk management of everything: Rethinking the politics of uncertainty. Demos.

Ritchie-Dunham, J. L. (2024). Agreements: Your choice. Vibrancy Publishing.

Star, S. L., & Strauss, A. (1999). Layers of silence, arenas of voice: The ecology of visible and invisible work. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 8(1–2), 9–30.

Strauss, A. (1988). The articulation of project work: An organizational process. The Sociological Quarterly, 29(2), 163–178.

Note: This text reflects conceptual research thinking. It does not describe or assess any specific organization. Examples and situations referenced are synthetic or composite and are used solely for analytical purposes.